The Neon-Lit Alleyways of Literary Revolution

So it’s the early 1980s. Synthesizers dominate the airwaves, personal computers are invading homes, and a new breed of science fiction is gestating in the minds of writers who’ve grown up with the threat of nuclear annihilation and the promises of a digital future. Welcome to the birth of cyberpunk, a subgenre that would go on to revolutionize not just science fiction, but our very perception of the future.

From Pulp Dreams to Silicon Nightmares

Cyberpunk didn’t spring fully formed from the head of William Gibson like some chrome-plated Athena. Its DNA can be traced back to the noir-tinged science fiction of the 1960s and ’70s. Authors like Philip K. Dick were already exploring the dark underbelly of technological progress in novels like “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” (later adapted into the cyberpunk classic film “Blade Runner”).

But cyberpunk as we know it truly began to coalesce with the publication of Vernor Vinge’s novella “True Names” in 1981. Vinge’s tale of hackers and virtual realities laid the groundwork for what was to come, painting a picture of a world where the lines between the physical and the digital were increasingly blurred.

Neuromancer: The Big Bang of Cyberpunk

If Vinge provided the kindling, William Gibson’s 1984 novel “Neuromancer” was the match that set the cyberpunk world ablaze. Gibson’s tale of a washed-up computer hacker hired for one last job captured the imaginations of readers and writers alike. With its gritty street-level view of a future dominated by mega-corporations and awash in cutting-edge technology, “Neuromancer” defined the cyberpunk aesthetic.

But what made “Neuromancer” truly revolutionary was its prose. Gibson’s writing crackled with energy, a staccato beat of neologisms and tech-speak that felt like it had been beamed in from the future. Who could forget that iconic opening line? “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.”

The Sprawl and Beyond

Gibson didn’t stop with “Neuromancer.” He expanded his vision of the future in two sequel novels, “Count Zero” and “Mona Lisa Overdrive,” collectively known as the Sprawl trilogy. These books further developed the cyberpunk ethos, exploring themes of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and the commodification of human consciousness.

But Gibson wasn’t the only one riding the cyberpunk wave. Authors like Bruce Sterling, with novels like “Schismatrix Plus” and “Islands in the Net,” were pushing the boundaries of the subgenre. Sterling’s work often focused on the societal implications of advanced technology, painting complex pictures of future cultures shaped by bioengineering and information networks.

Hardwired for Rebellion

What set cyberpunk apart from previous science fiction wasn’t just its focus on technology, but its attitude. Cyberpunk protagonists weren’t square-jawed heroes or brilliant scientists. They were outcasts, criminals, and misfits – the kind of people usually relegated to supporting roles in traditional SF.

Take Walter Jon Williams’ “Hardwired,” for example. Its protagonists are a drug-running former fighter pilot and a “cowboy” who can jack his consciousness directly into computer systems. They’re not trying to save the world; they’re just trying to survive in it, and maybe stick it to the corporations along the way.

This focus on the fringes of society gave cyberpunk a punk rock edge that resonated with readers who’d grown disillusioned with the utopian visions of earlier science fiction. Cyberpunk said, “The future’s going to be a mess, but there’s still room for rebellion.”

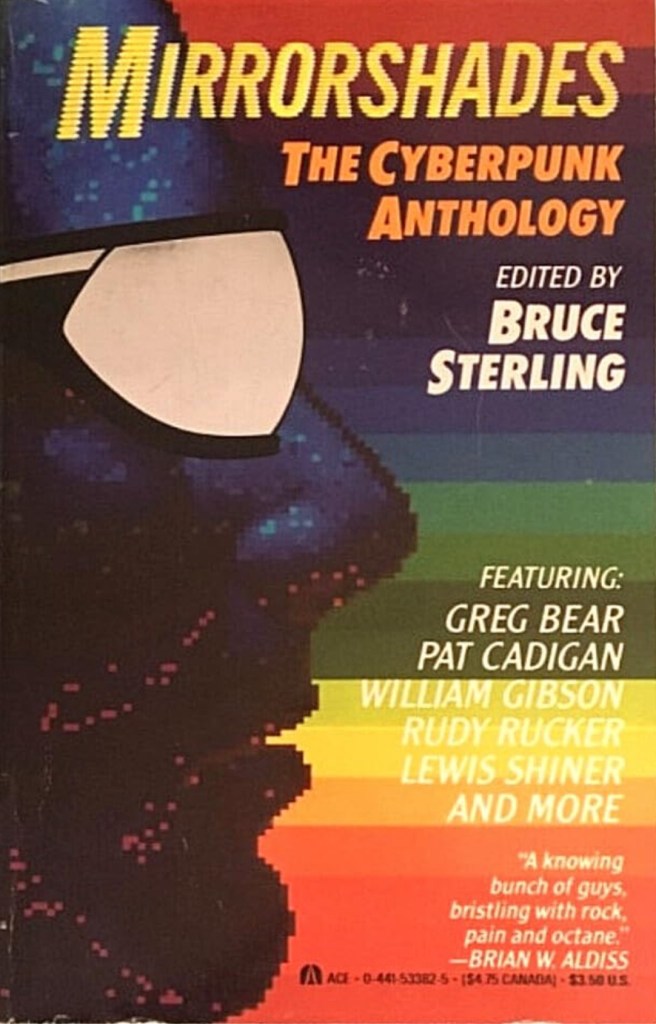

The Mirrorshades Manifesto

In 1986, Bruce Sterling edited an anthology called “Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology.” In his preface, Sterling laid out what he saw as the core themes of cyberpunk:

- The integration of technology and human biology

- The influence of drugs and computer technology on human consciousness

- The power of multinational corporations and the decline of traditional nation-states

- The fusion of high and low culture

This “Mirrorshades Manifesto” helped to codify what cyberpunk was all about, and provided a roadmap for authors looking to explore this new literary territory.

Beyond Blade Runners: Cyberpunk in Other Media

While cyberpunk was born in literature, it quickly spread to other media. Ridley Scott’s 1982 film “Blade Runner,” based on Philip K. Dick’s novel, established the visual aesthetic of cyberpunk cinema before the term even existed. Its rain-soaked, neon-lit cityscapes became the de facto image of the cyberpunk future.

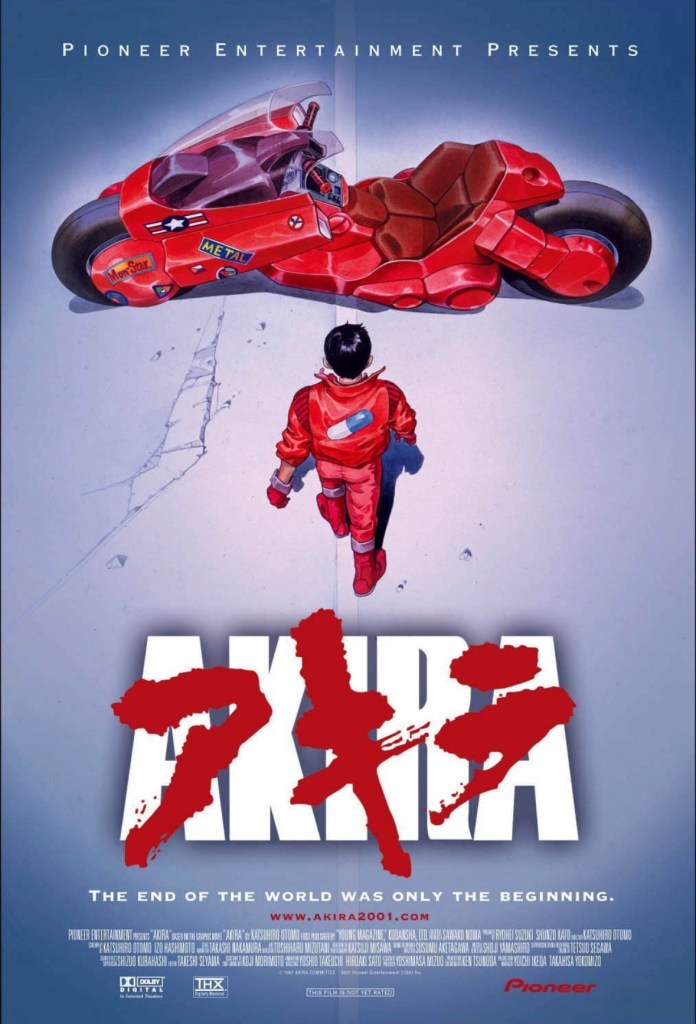

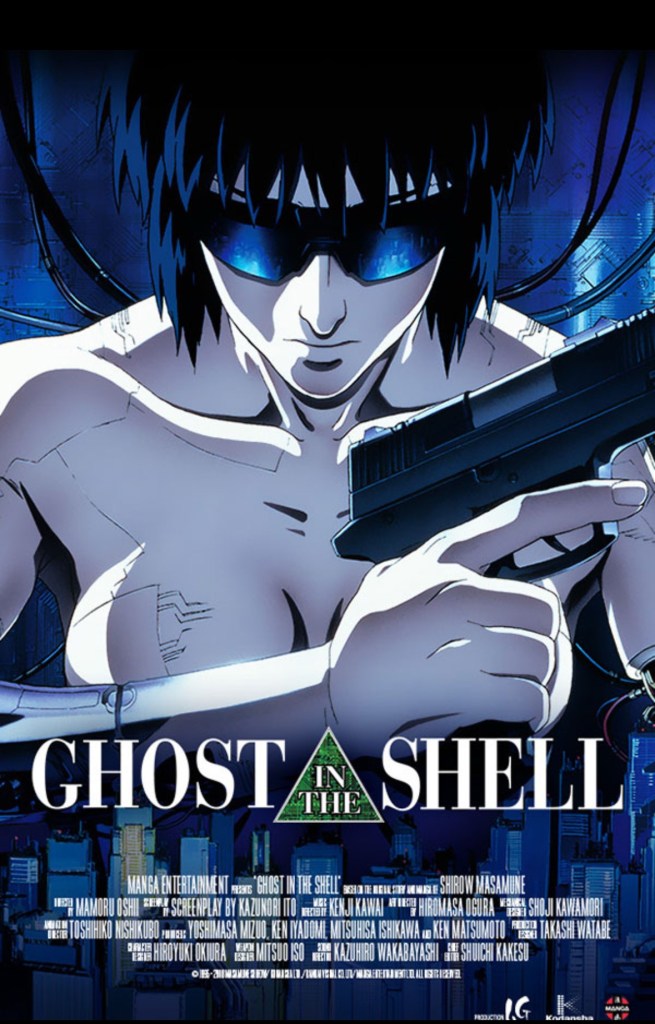

Anime and manga embraced cyberpunk wholeheartedly, with works like Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira” and Masamune Shirow’s “Ghost in the Shell” becoming influential classics in their own right. These Japanese works often brought a unique perspective to cyberpunk themes, exploring ideas of posthumanism and the nature of consciousness in ways that Western authors hadn’t.

The Cyberpunk Revolution

As the ’80s rolled into the ’90s, cyberpunk continued to evolve. Authors like Neal Stephenson pushed the boundaries of the subgenre with novels like “Snow Crash,” which injected a hefty dose of satire and linguistic theory into the cyberpunk formula. Pat Cadigan, often called “the Queen of Cyberpunk,” explored issues of gender and identity in works like “Synners” and “Fools.”

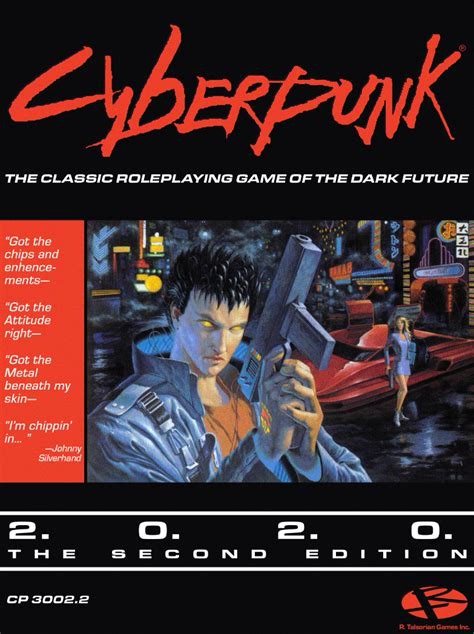

Meanwhile, role-playing games like “Cyberpunk 2020” and “Shadowrun” allowed fans to immerse themselves in cyberpunk worlds, further spreading the subgenre’s influence.

The Legacy of Cyberpunk

As we stand in the 2020s, many of cyberpunk’s once-outlandish predictions have become reality. We carry powerful computers in our pockets, mega-corporations wield unprecedented power, and the line between the virtual and the real grows ever thinner.

But cyberpunk’s influence extends far beyond its predictive power. Its aesthetics and themes have permeated popular culture, from fashion to music to film. The “Matrix” films brought cyberpunk concepts to mainstream audiences, while TV shows like “Mr. Robot” and “Black Mirror” continue to explore cyberpunk themes in contemporary settings.

In literature, cyberpunk has evolved into various “post-cyberpunk” forms. Authors like Charles Stross, Richard K. Morgan, and Hannu Rajaniemi push the technological envelope even further, while others like Paolo Bacigalupi blend cyberpunk themes with ecological concerns in what’s sometimes called “solarpunk.”

Jacking Out: The Enduring Appeal of Cyberpunk

So why does cyberpunk continue to resonate with readers and viewers decades after its inception? Perhaps it’s because the future it envisioned feels more relevant than ever. In a world of deepfakes, cryptocurrency, and virtual reality, the lines between the real and the virtual are increasingly blurred.

Or maybe it’s because cyberpunk, at its core, is about the human spirit’s resilience in the face of overwhelming technological and social change. It tells us that no matter how advanced our tools become, there will always be rebels, hackers, and dreamers pushing against the system.

As we navigate our own increasingly cyberpunk present, the works of Gibson, Sterling, and their contemporaries continue to serve as both warning and inspiration. They remind us to stay vigilant, to question authority, and to never stop imagining possible futures – both utopian and dystopian.

So, ready to dive into the neon-lit world of cyberpunk? Here are a few classic novels to get you started:

- “Neuromancer” by William Gibson

- “Snow Crash” by Neal Stephenson

- “Synners” by Pat Cadigan

- “Islands in the Net” by Bruce Sterling

- “Hardwired” by Walter Jon Williams

Remember: the future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comments are closed.