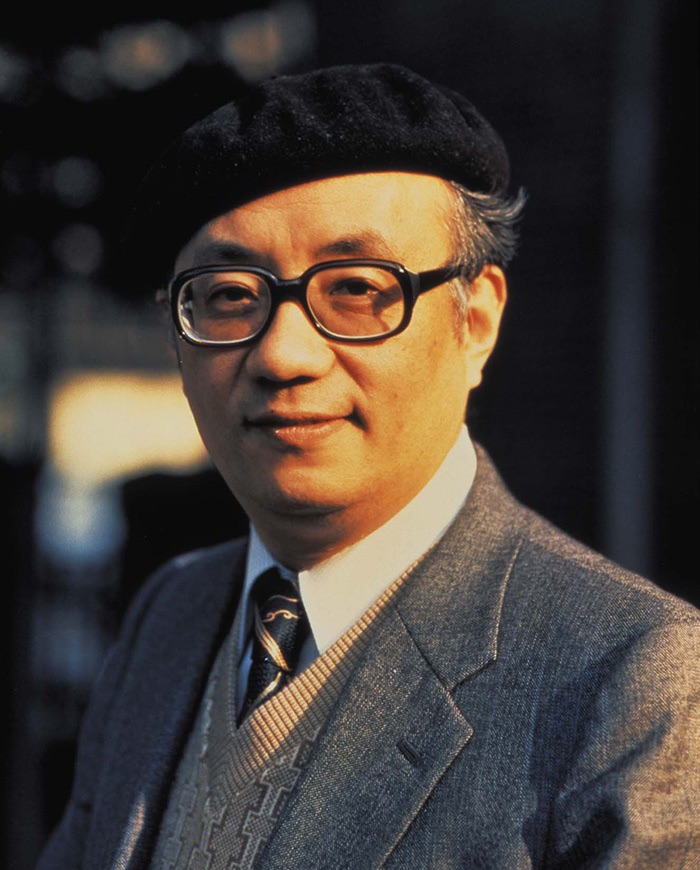

Osamu Tezuka, a 20th-century pop culture god (he was called ‘the god of Manga’ – manga no kamisama, after all), uniquely combined the precision of medical science with the boundless creativity of visual storytelling. Born in 1928 in Osaka, Japan, Tezuka represented a unique intersection of scientific rigor and artistic innovation, characteristics that would profoundly shape his approach to manga, and eventually, anime.

While studying medicine at Osaka University, Tezuka was already establishing himself as a revolutionary manga artist. This dual path—medical student by day, manga creator by night—was not merely a quirk of biography but a fundamental aspect of his creative DNA. His medical training provided a scientific lens through which he examined humanity, technology, history, and existential questions, themes that would become hallmarks of his science fiction works.

Cinematic Storytelling: A New Visual Language

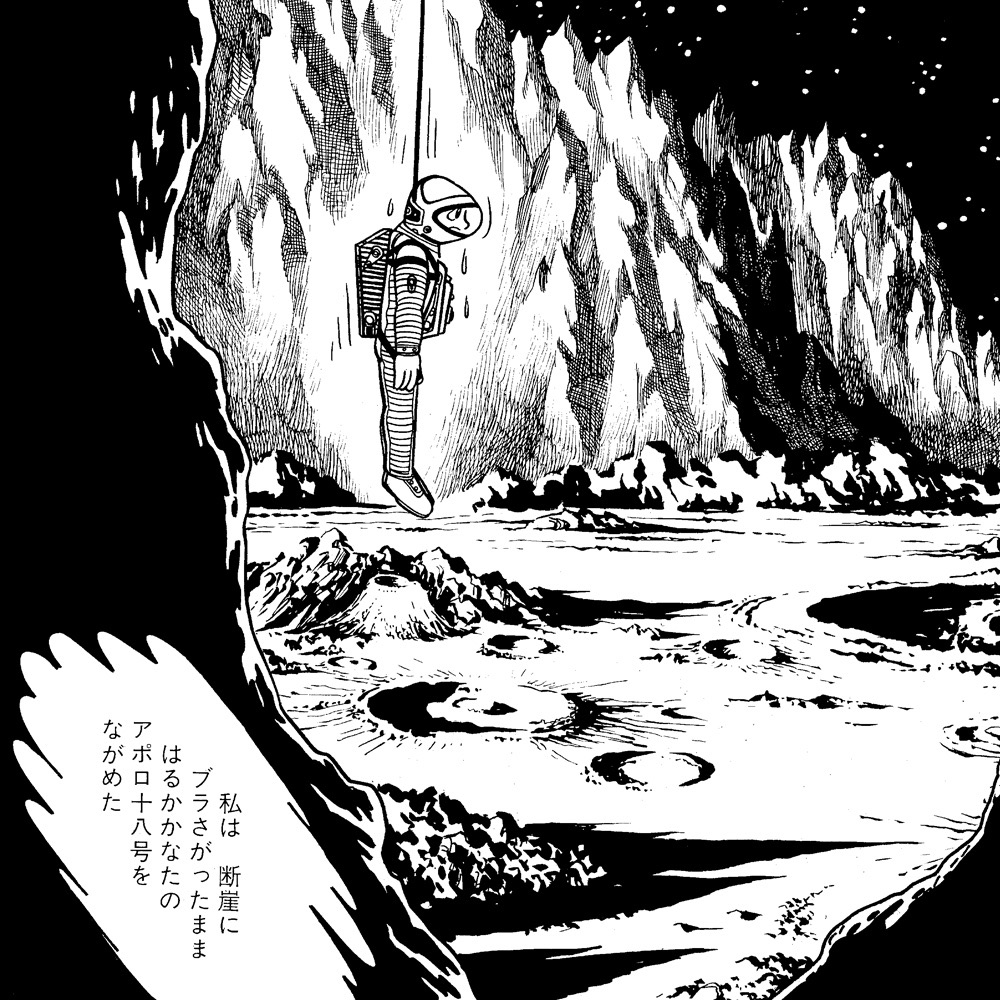

Tezuka didn’t just create manga; he reinvented the medium. Before his emergence, Manga was predominantly static and illustrative. Tezuka introduced cinematic techniques that transformed comic storytelling, borrowing visual language from film to create dynamic, fluid narratives. His panel layouts suggested movement, perspective, and emotional depth unprecedented in Japanese comics.

This revolutionary approach wasn’t merely aesthetic. By treating each panel like a film frame, Tezuka could convey complex emotional landscapes and philosophical concepts with unprecedented sophistication. Characters weren’t just drawn; they were choreographed through visual storytelling that anticipated the narrative complexity of modern graphic novels.

Philosophical Foundations: Science Fiction as Ethical Exploration

At the heart of Tezuka’s science fiction lay profound philosophical inquiries. His works weren’t escapist fantasies but nuanced explorations of humanity’s relationship with technology, consciousness, and moral complexity.

Three Seminal Works of Science Fiction

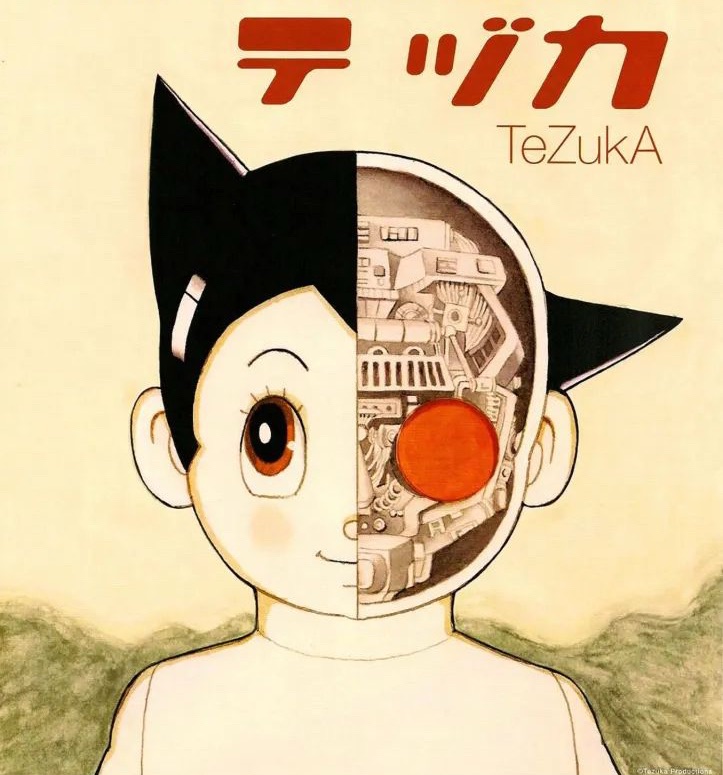

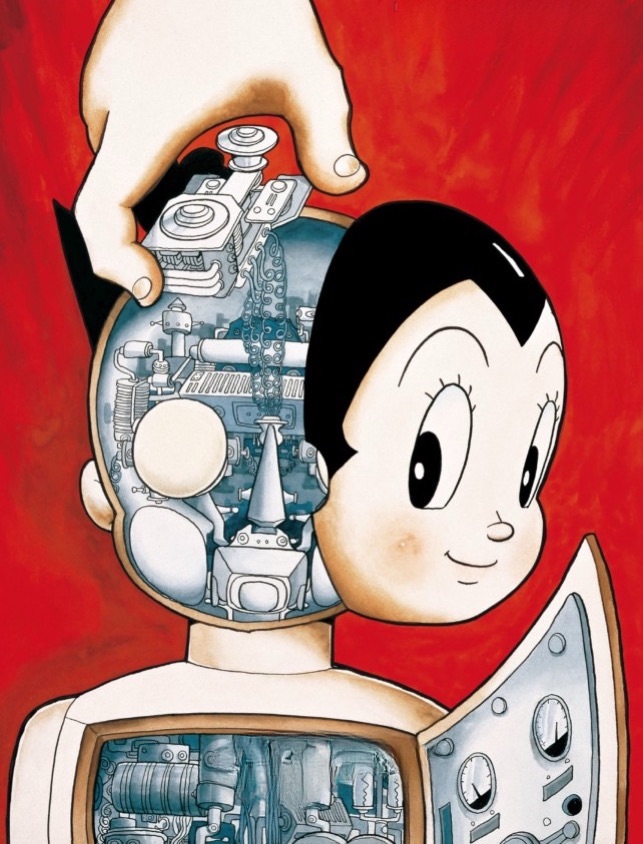

Astro Boy: Humanity Beyond Biology

“Tetsuwan Atomu” (Astro Boy), first serialized in 1952, epitomized Tezuka’s approach. The series followed Atom, a robot possessing human emotions, who constantly navigated the blurry boundaries between artificial and organic life. Through Atom’s experiences, Tezuka challenged readers to reconsider fundamental questions: What constitutes consciousness? Can empathy exist beyond biological origins?

Astro Boy wasn’t merely entertainment but a philosophical thought experiment. Each narrative arc explored different dimensions of artificial intelligence’s ethical implications, decades before such discussions entered mainstream technological discourse.

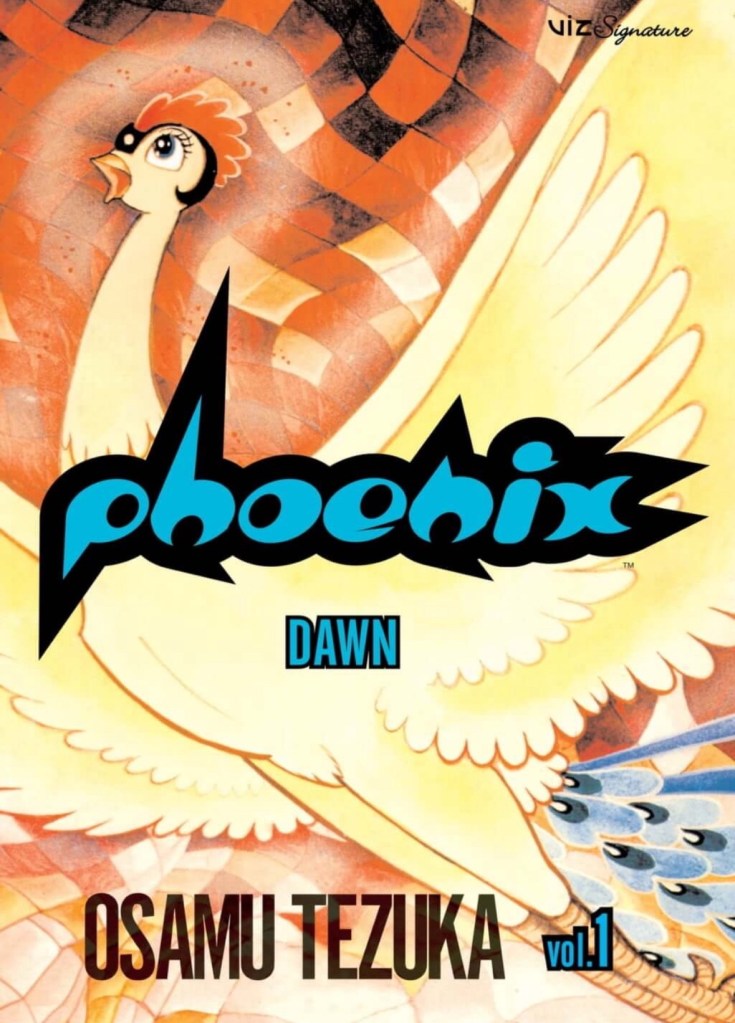

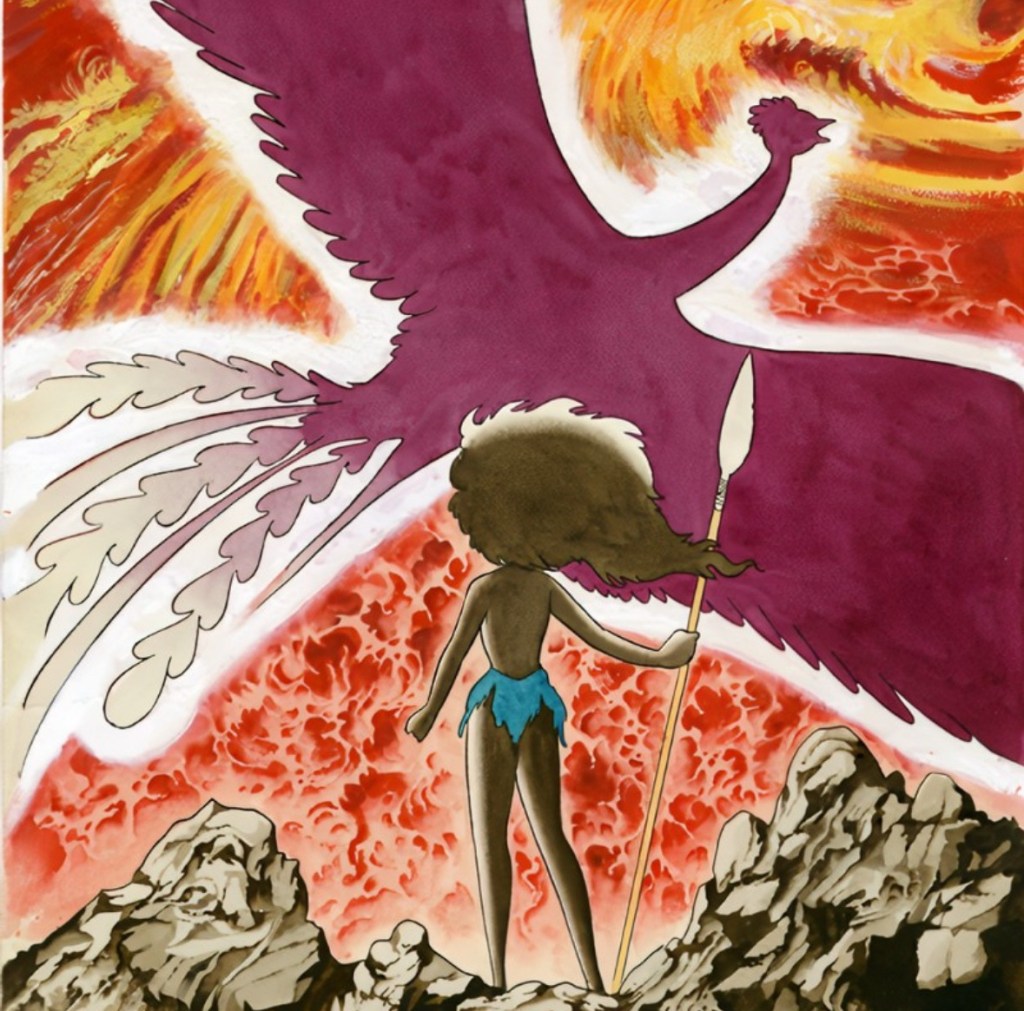

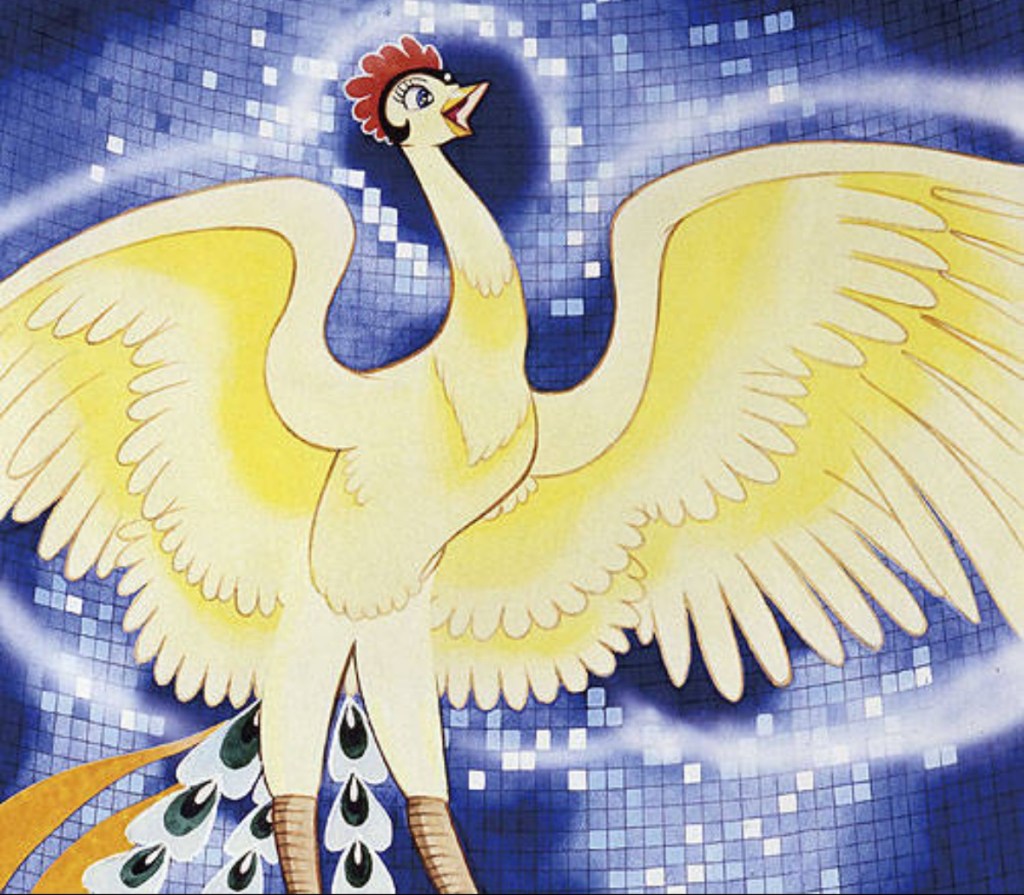

Phoenix: The Eternal Cycle of Existence

If Astro Boy represented Tezuka’s exploration of technological consciousness, “Phoenix” represented his most ambitious philosophical work. Spanning multiple historical periods and narrative styles, the series used the mythical phoenix as a metaphorical lens examining life, death, and rebirth.

Each story within the Phoenix cycle investigated human nature from different perspectives—historical, cultural, and metaphysical. By fragmenting traditional narrative structures, Tezuka created a kaleidoscopic meditation on existence that transcended conventional storytelling.

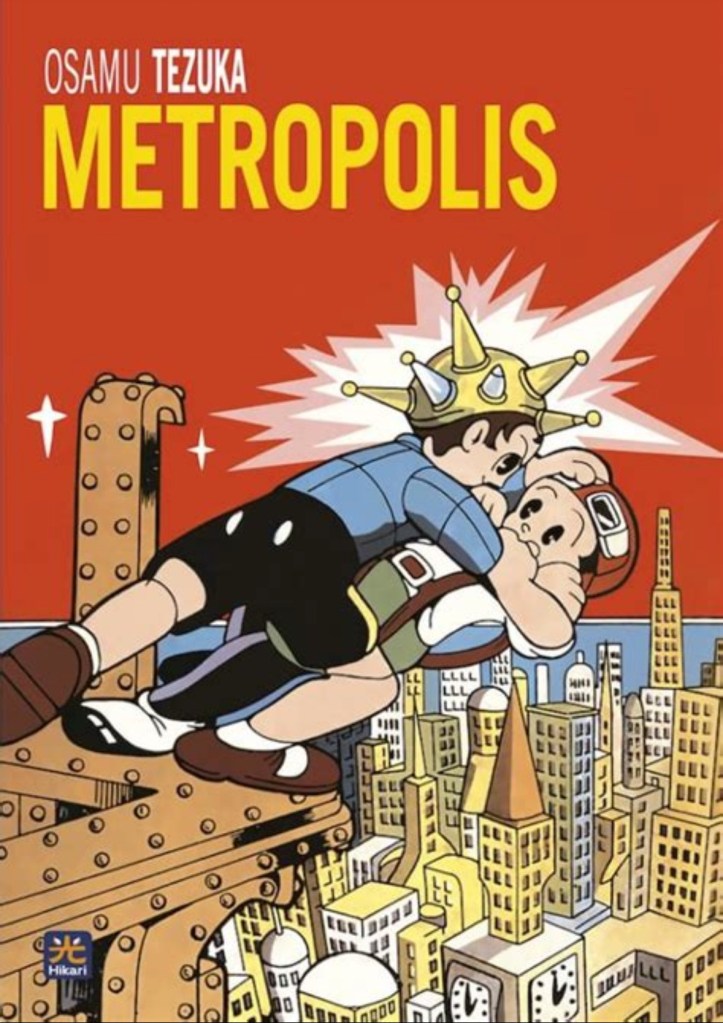

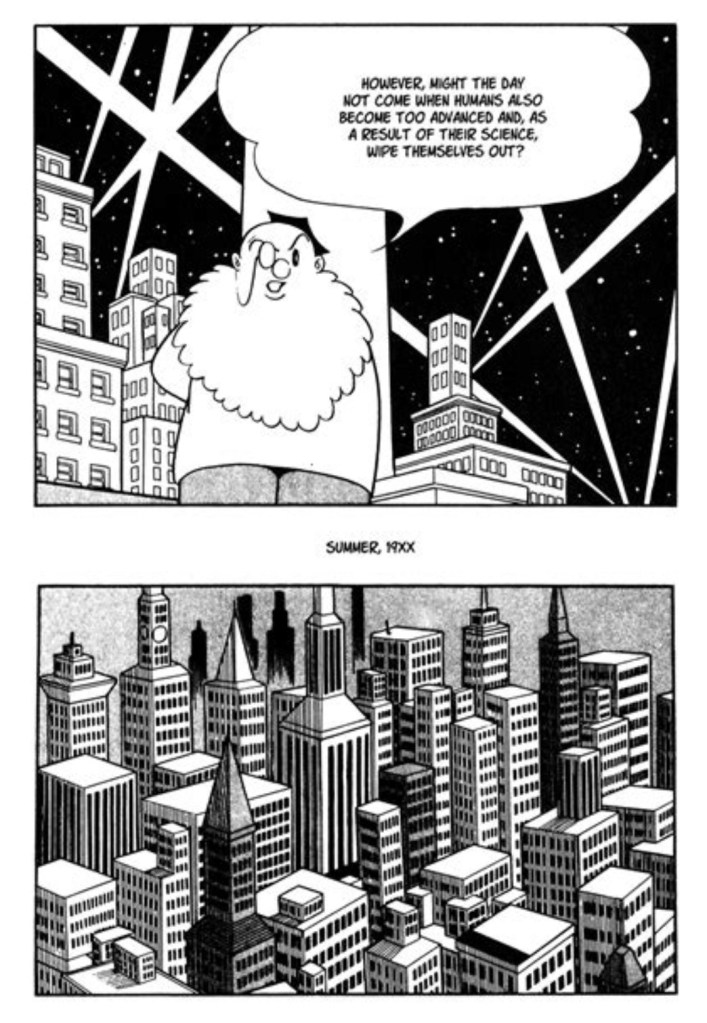

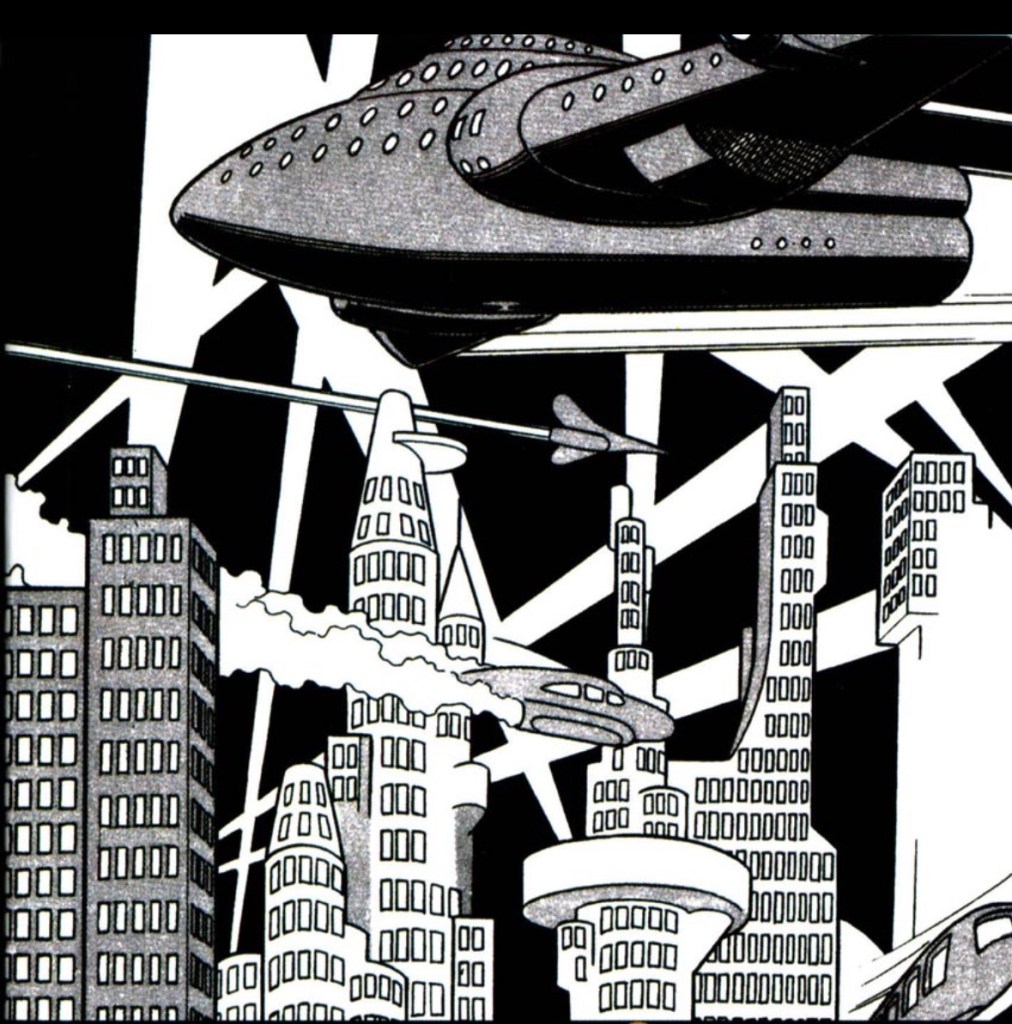

Metropolis: Societal Critique through Speculative Fiction

Tezuka’s science fiction wasn’t escapist—it was incisive social commentary. Works like “Metropolis” used futuristic settings to dissect contemporary social structures, particularly class inequality and technological alienation.

In “Metropolis,” humanoid robots serve as metaphorical representations of marginalized populations, their struggles mirroring real-world social dynamics. The narrative challenged readers to recognize systemic inequalities, using science fiction as a powerful allegorical tool.

Global Influence

Tezuka’s impact extended far beyond Japanese manga. He influenced generations of artists worldwide, including Western comic creators and animators. His narrative techniques and philosophical depth transformed how sequential art could communicate complex ideas.

Artists like Shotaro Ishinomori, Go Nagai, and Akira Toriyama directly credited Tezuka’s innovations as foundational to their own work. In the West, comic book creators recognized Tezuka as a pivotal figure who elevated graphic storytelling from disposable entertainment to a serious artistic medium.

Tezuka’s Vision

As artificial intelligence, robotics, and biotechnology advance, Tezuka’s speculative narratives seem increasingly prophetic. The ethical dilemmas he explored in the 1950s and 1960s—the nature of consciousness, technological empathy, societal integration of artificial beings—remain at the forefront of contemporary technological discourse.

Tezuka wasn’t just predicting technological futures; he was providing a humanistic framework for understanding our evolving relationship with technology. His works remind us that scientific progress is fundamentally a human story, defined by moral complexity rather than simple technological determinism.

Coda

Osamu Tezuka was more than a manga artist. He was a philosopher, a social critic, and a visionary who used the seemingly humble medium of manga to explore humanity’s most profound questions. By blending scientific knowledge, artistic innovation, and deep philosophical inquiry, he transformed science fiction from genre entertainment into a sophisticated mode of cultural expression.

His works continue to challenge and inspire, proving that true artistic innovation transcends media, genre, and historical moment.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great reading, thank you!

I’ma big fan of his since watching Astro Boy as a kid with my Mum, it was the only animated show she genuinely enjoyed because of its focus on values like empathy, kindness, and tolerance. I kinda just loved the robots and visuals 😅

I can also highly recommend his Buddha series. The story is epic and affecting and the artwork is incredible. I usually read through manga and graphic novels quickly, but I made a point of pausing on each page and really absorbing the visuals.

It’s amazing how there’s more emotion and humanity in Tezuka’s manga than in most live action films.

LikeLike