As I sit here, flipping through my old copy of Enki Bilal’s Nikopol Trilogy, I’m struck by an overwhelming sense of déjà vu. It’s been a decade since I last immersed myself in this surreal, dystopian world, yet the images and themes feel as fresh and relevant as ever. In fact, I’d argue that Bilal’s masterpiece has only grown more poignant with time, its prescient vision of a corrupt, decaying future resonating even more strongly in our current era of political upheaval and environmental crisis.

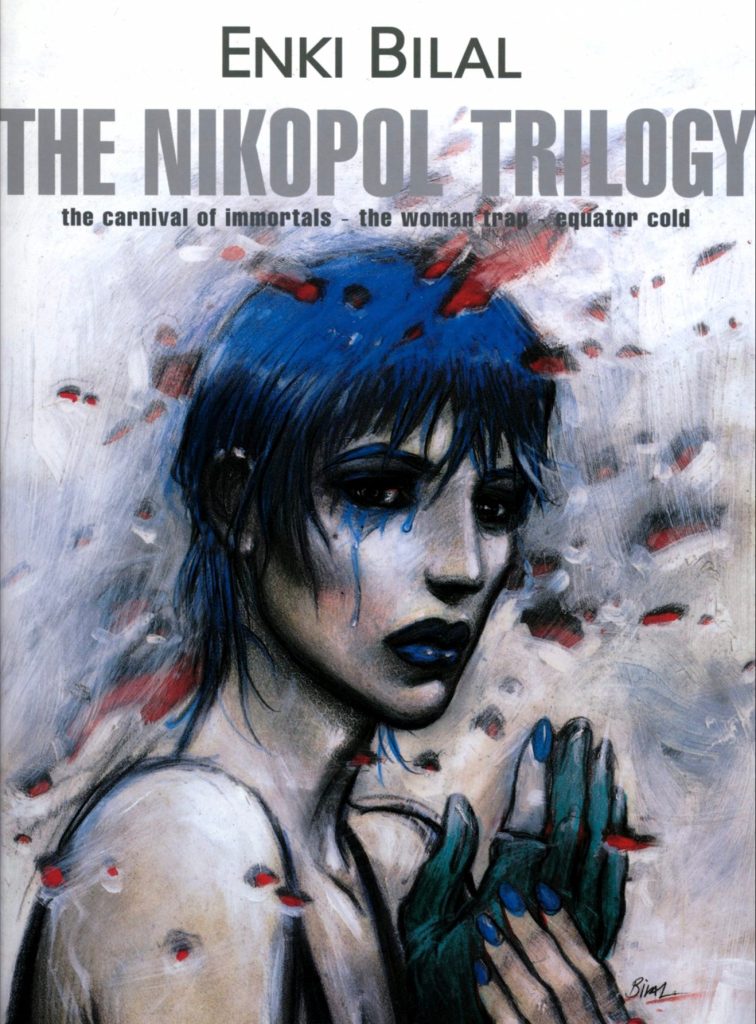

For those unfamiliar with this cornerstone of European graphic novels, allow me to set the stage. The Nikopol Trilogy, created by Yugoslavian-born French artist Enki Bilal, consists of three interconnected volumes: “La Foire aux immortels” (The Carnival of Immortals, 1980), “La Femme piège” (The Woman Trap, 1986), and “Froid Équateur” (Cold Equator, 1992). These works were later compiled into a single volume in 1995 and translated into English, introducing Bilal’s unique vision to a broader audience.

A World Both Alien and Familiar

The trilogy plunges us into a dystopian Paris of 2023 (a date that seemed impossibly distant when I first read the series, but now looms uncomfortably close). We follow Alcide Nikopol, an astronaut who returns to Earth after 30 years in cryogenic exile, only to find a world transformed beyond recognition. Paris is ruled by a fascist regime, the streets are populated by bizarre aliens, and a giant pyramid hovers ominously above the city, home to a pantheon of squabbling Egyptian gods.

It’s a premise that could easily veer into the realm of the ridiculous, but in Bilal’s capable hands, it becomes a vehicle for exploring deeply human themes. The fusion of mythological elements with futuristic technology creates a world that feels both alien and eerily familiar, a funhouse mirror reflection of our own society’s struggles with authoritarianism, environmental degradation, and the search for meaning in an increasingly chaotic world.

Here follows a detailed breakdown of the events in each colume:

- The Carnival of Immortals (La Foire aux immortels)

2023: Alcide Nikopol, an astronaut exiled into cryogenic stasis for 30 years after opposing a war with the Sino-Soviet coalition, crash-lands back on Earth. He awakens in a drastically changed Paris ruled by a fascist regime under Governor Jean-Ferdinand Choublanc. The city is a dystopian nightmare filled with aliens and plagued by environmental decay.

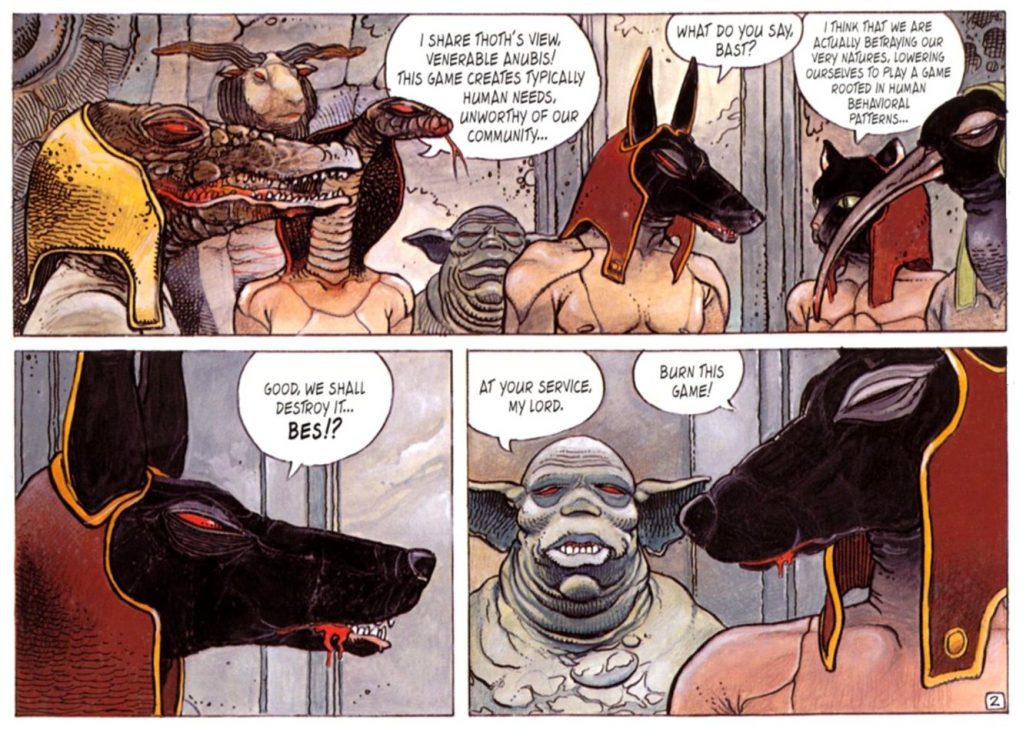

Above Paris hovers a massive pyramid inhabited by Egyptian gods who have returned to Earth but are stranded due to a lack of fuel. Among them is Horus, a rebellious and vengeful god who refuses to cooperate with his fellow deities. Seeking to regain power and oppose the gods’ control, Horus possesses Nikopol’s body to use him as a pawn in his schemes.

Horus manipulates Nikopol into infiltrating Parisian politics, ultimately overthrowing Choublanc. However, Nikopol struggles to retain his autonomy as Horus exerts control over his body. Amid this chaos, Nikopol discovers he has a son—Niko—who looks identical to him due to the time gap caused by his cryogenic stasis. - The Woman Trap (La Femme piège)

Set two years later in 2025, the second volume shifts focus to Jill Bioskop, a blue-haired journalist grappling with her fractured sense of reality due to mind-enhancing drugs. Jill serves as the narrative anchor in this installment, which takes on a more introspective and noir tone.

Jill becomes entangled with Nikopol and Horus as their paths cross during her investigation into political corruption and conspiracies involving the gods. Her disjointed perception of time and reality mirrors the fragmented nature of the world around her. The story delves deeper into themes of identity and memory while continuing to explore the interplay between humans and gods. - Cold Equator (Froid Équateur)

The final volume takes place in 2034 and brings all major characters—Nikopol, Niko (his son), Horus, and Jill Bioskop—to an African free-trade zone. This bizarre setting is characterized by surreal elements such as chessboxing tournaments (a hybrid sport introduced in this story) and chaotic political machinations.

Nikopol and Niko’s identities blur further as they are mistaken for one another due to their identical appearances. This literal doubling reflects ongoing themes of fractured identity and existential confusion. Meanwhile, Horus continues his manipulative schemes but faces consequences for his rebellion against his fellow gods.

The narrative becomes increasingly abstract, blending allegory with satire as it critiques societal structures, human greed, and environmental collapse. The trilogy concludes with an ambiguous resolution that reflects on humanity’s capacity for resilience amidst chaos.

The Power of Bilal’s Artistry

Revisiting the trilogy after so many years, I’m struck anew by the raw power of Bilal’s artwork. His style is unmistakable – gritty, textured, and atmospheric, with a muted color palette that perfectly captures the bleakness of his dystopian vision. Yet within this somber framework, moments of surreal beauty emerge, like flashes of color in a grayscale world.

Take, for example, the character of Jill Bioskop, the blue-haired journalist introduced in “The Woman Trap.” Her vibrant locks stand out starkly against the drab cityscape, a visual metaphor for her role as a disruptive force in the narrative. Bilal’s attention to detail is remarkable – every line on a character’s face, every crack in a decaying building, tells a story of its own.

What’s particularly impressive is how Bilal’s art style has aged. In an era where digital art dominates the comic landscape, there’s something refreshingly tactile about his hand-drawn panels. The imperfections and idiosyncrasies of his linework lend a human touch to even the most fantastical scenes, grounding the narrative in a tangible reality.

Themes That Resonate Across Time

Jumping back into the trilogy’s intricate plot, I’m struck by how many of its themes feel even more relevant today than they did a decade ago. The specter of totalitarianism that looms over Bilal’s Paris seems chillingly prescient in our current political climate. The environmental decay that serves as a backdrop to the action no longer feels like a distant possibility, but a looming threat.

But it’s not just these broad societal issues that give the Nikopol Trilogy its staying power. At its core, this is a deeply human story, grappling with questions of identity, memory, and the nature of reality itself. The character of Nikopol, whose body is periodically possessed by the god Horus, serves as a powerful metaphor for the fragmentation of self in the face of trauma and displacement.

Similarly, Jill Bioskop’s struggle with drug-induced memory loss and altered perceptions feels like a eerily prophetic exploration of our current concerns about the impact of technology on our minds and memories. In an age of information overload and digital manipulation, her story takes on new layers of meaning.

The Blending of Genres and Ideas

One of the aspects of the Nikopol Trilogy that I’ve come to appreciate even more over time is its fearless blending of genres and ideas. Bilal effortlessly weaves together elements of science fiction, political satire, mythology, and surrealist art into a narrative tapestry that defies easy categorization.

This genre-bending approach allows Bilal to explore complex ideas from multiple angles. The presence of Egyptian gods in a futuristic setting, for instance, becomes a vehicle for examining the role of religion and mythology in shaping human society. The gods, with their petty squabbles and manipulations, serve as a darkly comic mirror to human power structures.

Similarly, the introduction of “chessboxing” – a hybrid sport that combines chess and boxing – in “Cold Equator” is more than just a quirky detail. It becomes a metaphor for the duality of human nature, the constant struggle between intellect and physicality, strategy and brute force. The fact that chessboxing has since become a real sport only adds to the trilogy’s prophetic mystique.

A Narrative That Rewards Revisiting

One of the joys of returning to the Nikopol Trilogy after so many years is discovering how much I missed on my first read-through. Bilal’s storytelling is dense and often opaque, with multiple narrative threads weaving in and out of focus. It’s a style that can be challenging at first, but rewards patient readers with layers of meaning and symbolism.

On this reading, I found myself paying closer attention to the smaller details – the snippets of poetry from Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du mal” that pepper the text, the recurring motifs of mirrors and reflections, the subtle visual clues that foreshadow later plot developments. These elements create a rich tapestry of meaning that invites multiple interpretations and rewards repeated readings.

The Influence of the Nikopol Trilogy

It’s hard to overstate the impact that the Nikopol Trilogy has had on the world of graphic novels and science fiction. Its unique blend of political commentary, surrealism, and dark humor has influenced countless creators in the decades since its publication. The 2004 film adaptation, “Immortel (Ad Vitam),” directed by Bilal himself, brought his vision to an even wider audience, though it diverges significantly from the source material.

But perhaps the trilogy’s most enduring legacy is the way it challenges readers to engage with complex ideas and uncomfortable truths. In a media landscape often dominated by simplistic narratives and easy answers, the Nikopol Trilogy stands as a testament to the power of art to provoke thought and spark imagination.

Coda

Re-reading The Nikopol Trilogy left me with a renewed appreciation for Bilal’s creative abilities. This is a work that has not just stood the test of time, but seems to grow more relevant with each passing year. Its exploration of themes like political corruption, environmental decay, and the fragmentation of identity feels more urgent than ever in our current global context.

What makes the trilogy truly timeless, however, is its deep engagement with the fundamental questions of what it means to be human. Through the experiences of Nikopol, Jill, and the other characters that populate this strange and beautiful world, we’re invited to reflect on our own struggles with identity, memory, and the search for meaning in a chaotic universe.

For new readers, the Nikopol Trilogy offers a challenging but rewarding journey into one of the most unique and thought-provoking worlds in graphic literature. For those of us returning to it after years away, it’s a chance to rediscover a work of art that continues to surprise, provoke, and inspire. In either case, it’s a testament to the enduring power of Enki Bilal’s vision – a story that feels as vital and relevant today as it did when it first appeared over four decades ago.

As our own world inches closer to the dystopian future Bilal imagined, the Nikopol Trilogy serves as both a warning and a beacon of hope. It reminds us of the power of art to illuminate the darkest corners of human experience, and to imagine new possibilities even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges. In doing so, it cements its place not just as a classic of graphic literature, but as a timeless exploration of the human condition itself.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.