Introduction: A Personal Reunion With a Sci-Fi Masterpiece

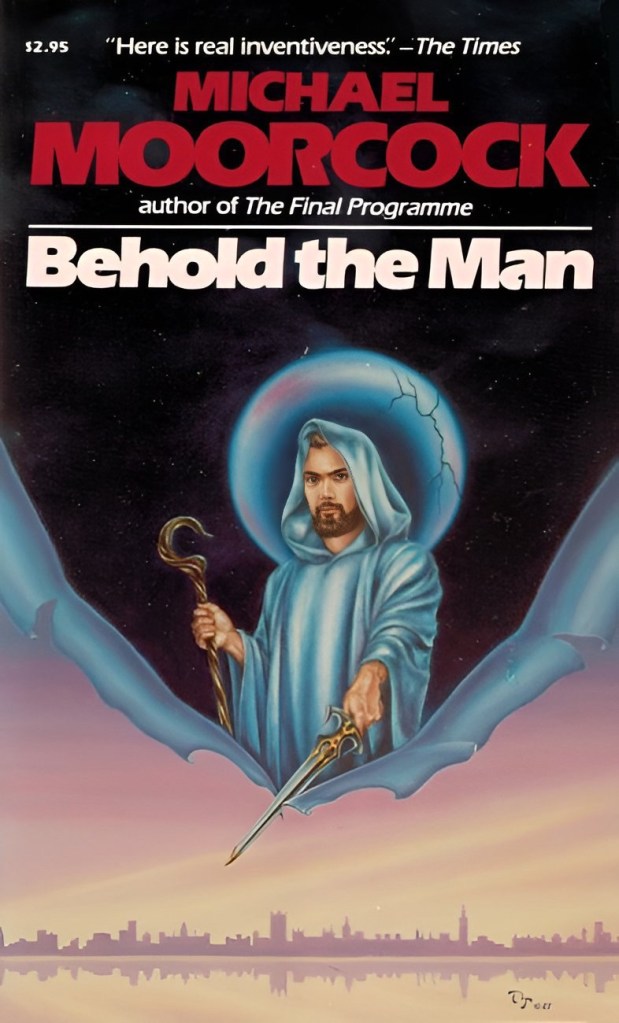

I remember the first time I encountered Michael Moorcock’s “Behold the Man” – I was barely into my twenties, arrogantly confident in my understanding of both science fiction and religion. The slim volume sat on a shelf in a second-hand bookstore near my campus, its provocative title calling out to me, challenging me to read it ASAP. It rewired my brain somewhat, after reading it that first time. Now, three decades later, I find myself drawn back to this literary time machine, and what a profound experience it has been.

“Behold the Man” is a novel that is as complex as it is nuanced – a multilayered exploration of psychology, existentialism, and the cyclical relationship between fact and myth. This isn’t just science fiction; it’s an existential trip wrapped in the trappings of time travel, a psychological excavation that uses religious history as its backdrop.

The Premise: Time Travel as Existential Exploration

For the uninitiated, “Behold the Man” follows Karl Glogauer, a troubled man from 1970s London who travels back in time to 28 AD Palestine. His mission seems straightforward – to witness the historical Jesus of Nazareth firsthand. But Moorcock, ever the literary provocateur, has no interest in crafting a straightforward narrative.

Upon arrival, Karl’s time machine – described as a “womb-like, fluid-filled sphere” (a rebirth metaphor that feels significantly more potent to me now than it did in my youth) – is destroyed. Injured and stranded, he’s rescued by John the Baptist and a group of Essenes who witness his arrival and believe him to be a prophet.

What follows is the novel’s central, shocking revelation: when Karl finally locates Mary and Joseph in Nazareth, their son Jesus is revealed to be a profoundly intellectually disabled man who can only repeat his own name. This discovery forces Karl to confront a profound existential crisis – and ultimately leads him to step into the role of Jesus himself, gathering followers, repeating parables from memory, and eventually orchestrating his own crucifixion.

The Character Study: Karl Glogauer as Existential Anti-Hero

Reading “Behold the Man” in middle age offers me a vastly different perspective on Karl Glogauer than I had in my twenties. What once seemed like an unnecessarily complex character now strikes me as one of fiction’s most fascinating psychological portraits – a quintessentially existentialist anti-hero.

Through flashbacks, Moorcock reveals Karl’s childhood traumas – an absent Austrian father, experiences of abuse, bullying – and his adult struggles with purpose and connection. His girlfriend Monica accurately identifies his messiah complex, his masochism, his indecisiveness. He’s overly emotional, quick to anger, prone to depression.

There’s something painfully authentic about Karl that resonates differently when you’ve lived long enough to recognize these patterns in yourself and others. His relationship with religion is particularly complex – despite having a Jewish mother, he wasn’t raised religiously yet develops an obsession with Christianity and Jesus Christ. His psychological associations are fascinating: “a silver cross = women; wooden cross = men” reveals a man whose religious symbolism is completely intertwined with his sexuality and identity.

As Monica observes during their arguments about faith and reason, Karl needs God in a way that places him at odds with the modern world. “This age of reason has no place for me,” Karl admits. “It will kill me in the end.” That line hit me like a thunderbolt this time around – the confession of a man who can’t reconcile his need for meaning with a world that increasingly rejects transcendence.

The Philosophical Dimensions: Existentialism as a Narrative

What escaped me entirely in my first reading was how thoroughly “Behold the Man” embodies existentialist philosophy. From its Wikipedia description as an “existentialist science fiction novel” to its thematic preoccupations, this is Moorcock’s literary engagement with Sartre, Camus, and their philosophical tradition.

Karl’s discovery that the historical Jesus is nothing like his Gospel portrayal exemplifies what Camus called “the absurd” – the confrontation between human meaning-seeking and a universe without inherent meaning. His response to this crisis demonstrates the existentialist emphasis on freedom, choice, and authentic commitment. Rather than abandoning his quest, Karl makes the extraordinary decision to become Jesus himself – to create meaning through his own choices and actions.

This illustrates Sartre’s famous dictum that “existence precedes essence” – Karl doesn’t begin as Jesus; he becomes Jesus through his choices. The novel explicitly articulates this principle: “Acting into a new way of thinking is always more effective than trying to think into a new way of acting. Perhaps this is the secret Jesus wanted to convey.” This strikes me now as the philosophical heart of the novel – the existentialist prioritization of action over contemplation, the belief that meaning emerges from what we do rather than what we think.

Fact and Myth: Beyond Simple Dichotomies

Perhaps the most sophisticated aspect of “Behold the Man” – and one I completely missed in my youth – is its exploration of the relationship between historical fact and mythological narrative. The novel doesn’t simply dismiss religious myths as falsehoods, nor does it uncritically accept them. Instead, it presents a cyclical, mutually constitutive relationship between fact and myth.

Karl’s conversation with Monica represents one of the novel’s most explicit engagements with this theme. She argues that “the myth is unimportant and that the impulse that creates it is the important thing.” This perspective is validated through Karl’s experiences, where he witnesses how the historical facts of Jesus’s life matter less than the psychological and social needs that the Jesus narrative fulfills.

By stepping into the role of Jesus, Karl literally embodies myth through human action. He transforms what might otherwise be dismissed as “mere myth” into a form of lived truth. As he contemplates his decision, he recognizes that he would be “bringing a myth to life, not changing history so much as infusing more depth and substance into history.”

This cyclical relationship becomes the novel’s most profound insight. As one reviewer notes, “there is a chicken-and-egg relationship between truth and myth: we fashion our own experience of truth from our collective beliefs; yet our collective beliefs influence how we construct our own realities.” This nuanced perspective transcends the simplistic fact/fiction dichotomy that often characterizes discussions of religious history.

Style, Structure, and Significance

Stylistically, “Behold the Man” showcases Moorcock at his literary best. The dual timeline structure, alternating between Karl’s past in London and his experiences in ancient Palestine, creates a rich psychological portrait while maintaining narrative momentum. This structure also underscores one of the novel’s central paradoxes: Karl’s experiences in Palestine occur both before and after his life in London, challenging conventional notions of causality.

What’s particularly striking is how Moorcock balances philosophical complexity with narrative drive. The novel never feels like a philosophical treatise disguised as fiction; rather, its existentialist themes emerge organically from character and plot. Moorcock’s prose is lean yet evocative, capturing both the psychological interiority of Karl and the stark physical realities of ancient Palestine.

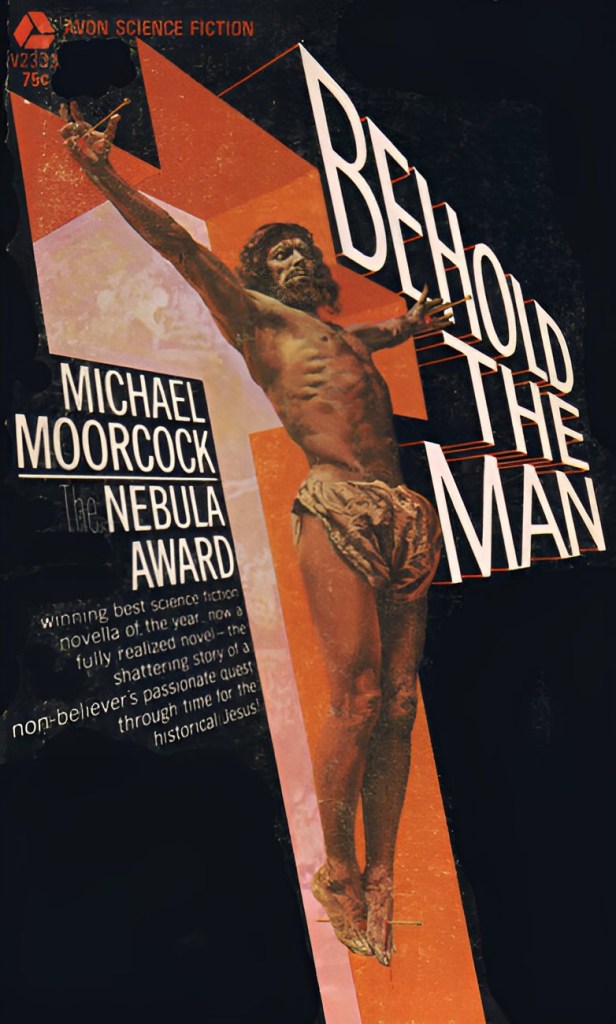

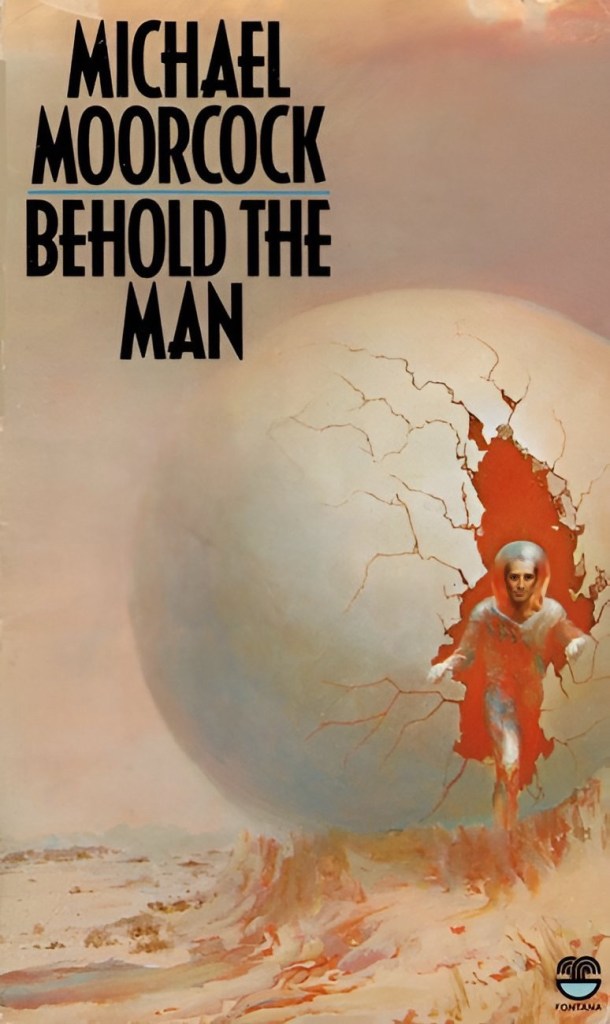

The novel’s significance extends beyond its Nebula Award win. As part of science fiction’s New Wave movement, it helped demonstrate that the genre could engage meaningfully with religious themes without either uncritical acceptance or dismissive rejection of religious traditions. Its influence can be seen in later works that tackle similar themes, from Philip K. Dick‘s “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch” to Mary Doria Russell’s “The Sparrow.”

Coda

Returning to “Behold the Man” after three decades has been a profound experience. What once seemed merely provocative now reveals itself as a work of remarkable philosophical and psychological depth. This is science fiction at its best – using speculative elements not as mere window dressing but as vehicles for exploring fundamental questions about human nature, meaning, and belief.

What makes the novel particularly remarkable is its ability to engage meaningfully with religious questions without offering simplistic answers. Neither a straightforward affirmation nor a dismissive critique of Christianity, it occupies an ambiguous middle ground that respects the psychological significance of religious belief while questioning its historical foundations.

In Karl Glogauer, Moorcock has created one of literature’s most fascinating protagonists – a deeply flawed individual whose neuroses and psychological wounds ultimately lead him to an act of radical self-sacrifice. His journey continues to challenge readers to reconsider not just religious history but the very categories through which we understand the relationship between historical fact and mythological narrative.

If you’ve never read “Behold the Man,” I urge you to. And if, like me, you found it in your youth, perhaps it’s time for a reunion. Some books simply change with time; the truly great ones reveal how much you’ve changed. Moorcock’s masterpiece falls firmly in this latter category.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.