Of all the science fiction films I’ve seen, few have left me as mentally exhausted—and spiritually energized—as Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 masterpiece Stalker. It’s not a typical SF flick with lasers and aliens and space battles. Hell, it barely qualifies as science fiction in the traditional sense. What it is, though, is a philosophical kick in the crotch wrapped in the trappings of a post-apocalyptic journey that’ll leave you questioning everything you thought you knew about desire, faith, and what it means to be human.

The Setup: Three Men Walk Into a Zone…

The premise sounds simple enough. There’s this place called the Zone—a forbidden area guarded by the military where the laws of physics supposedly don’t apply. Twenty years ago, something happened there. Maybe a meteorite hit. Maybe aliens visited. Nobody knows for sure, and the film doesn’t care to explain. What matters is that at the Zone’s center lies a Room that grants your deepest, most honest desire.

Our guide into this wasteland is the Stalker, played with haunting intensity by Alexander Kaidanovsky. He’s a weathered true believer who makes his living leading clients through the Zone’s invisible dangers. This time, he’s bringing along two intellectuals: a cynical Writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn) seeking inspiration for his dried-up creativity, and a Professor (Nikolai Grinko) who claims he wants to win a Nobel Prize.

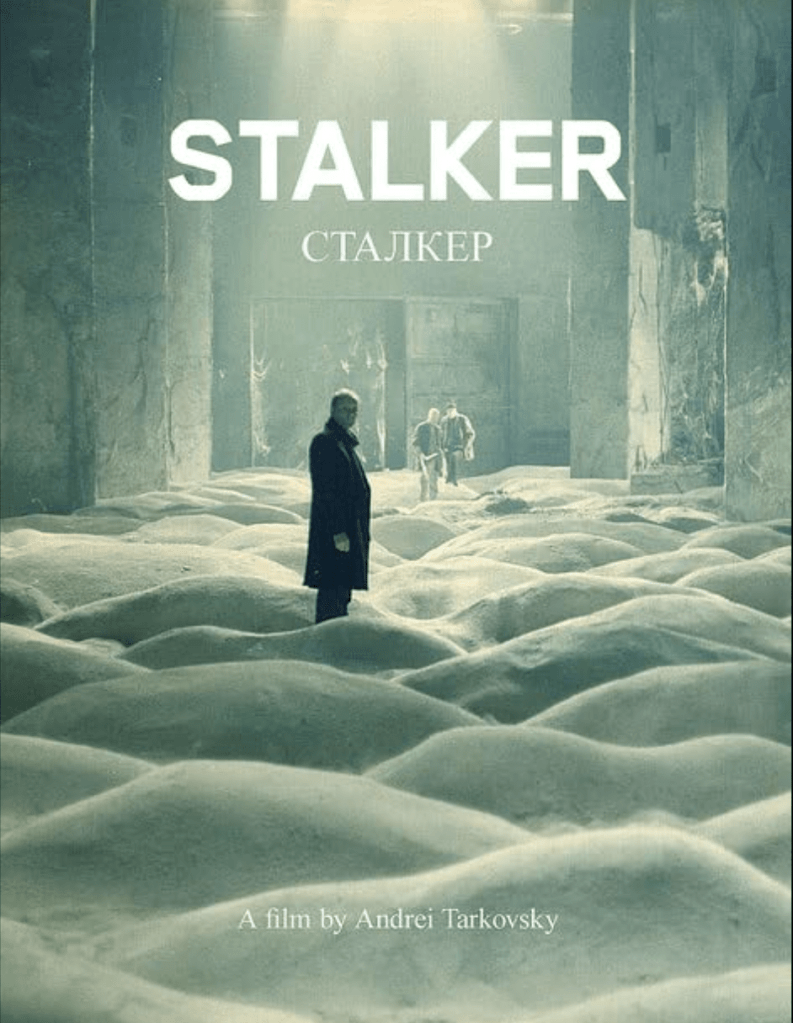

What unfolds over the next 160 minutes (yeah, it’s a long one) is less an adventure and more a psychological excavation. The three men trudge through industrial ruins, abandoned tunnels, and overgrown fields, all while the Stalker warns them about invisible dangers that may or may not exist. They throw metal nuts tied to bandages to test safe paths. They take circuitous routes to avoid threats only the Stalker can sense. The tension comes not from jump scares or special effects, but from the crushing weight of existential dread that permeates every frame.

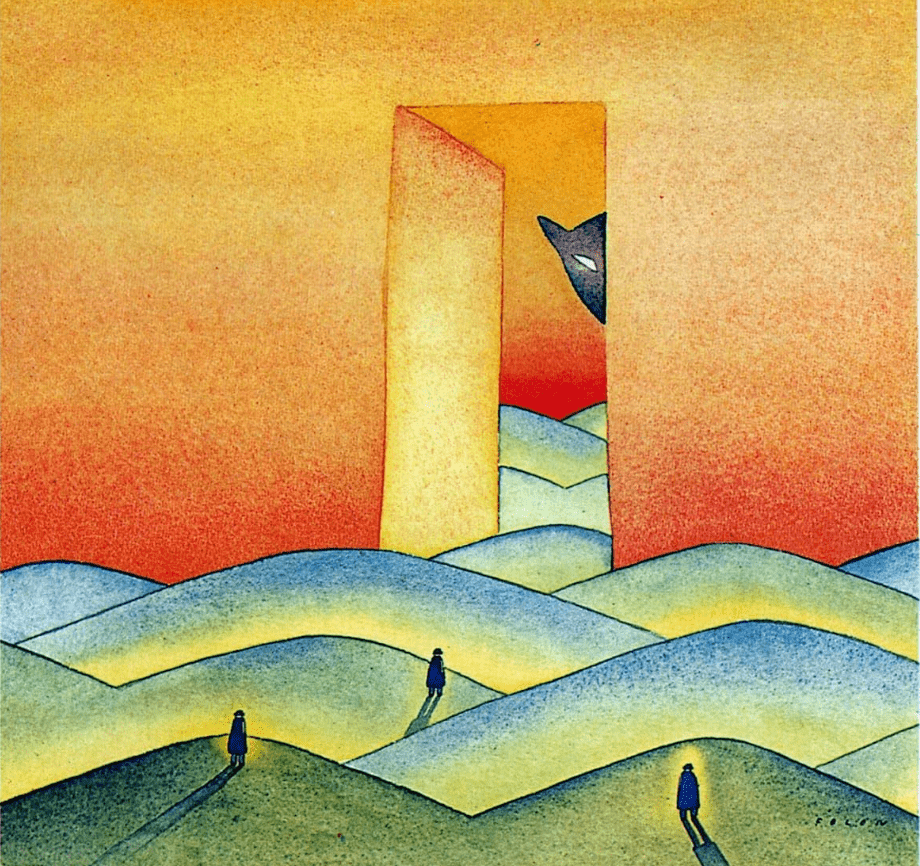

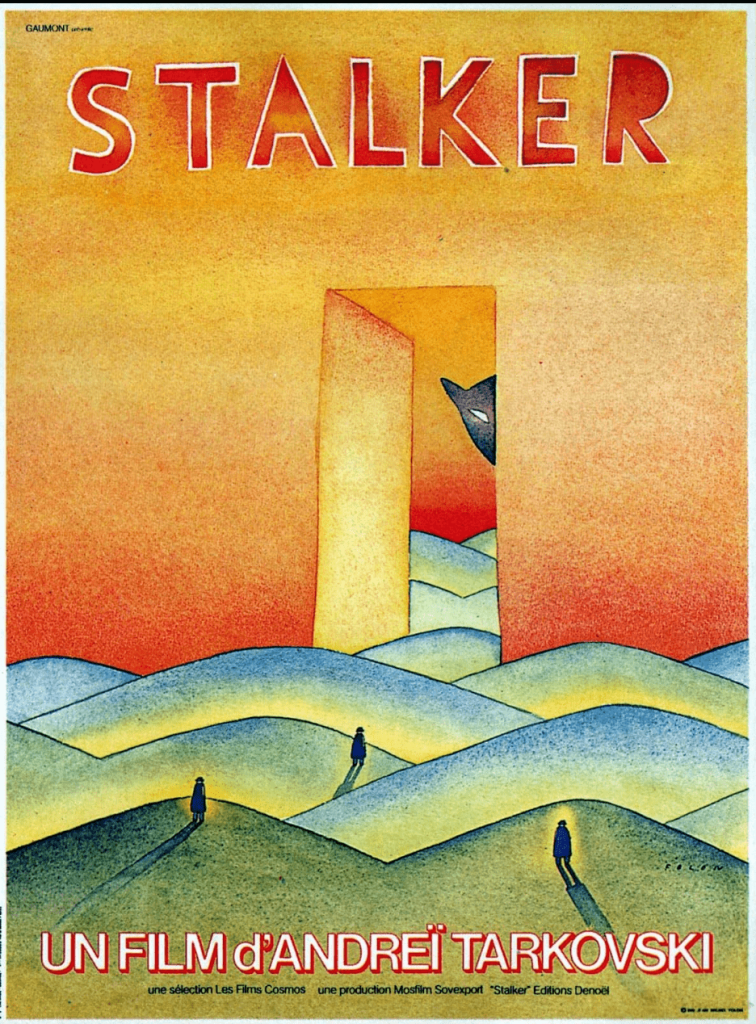

A Journey Through Tarkovsky’s Visual Poetry

Before I dig into the philosophical meat of this thing, I need to talk about how goddamn beautiful it is. Cinematographer Alexander Knyazhinsky (who tragically died during production, along with several other crew members—some say from exposure to toxic chemicals at the shooting locations) crafts images that burn themselves into your retinas. The film shifts from sepia-toned scenes in the outside world to rich, almost supernatural colors once we enter the Zone. Water is everywhere—dripping, pooling, flowing—turning the landscape into something primordial and dreamlike.

There’s this one shot that still haunts me: the camera slowly tracks over a shallow pool littered with debris—coins, syringes, religious icons, a gun—while Ravel’s “Bolero” plays. It’s like archaeology of the soul, all these discarded objects of human desire and fear submerged in murky water. Tarkovsky holds on these images far longer than any reasonable director would, forcing you to really look, to meditate on what you’re seeing.

The sound design is equally mesmerizing. The Zone has its own acoustic signature—distant metallic groans, water drops echoing in vast spaces, the crunch of footsteps on broken glass. Eduard Artemyev’s electronic score appears sparingly but effectively, creating an atmosphere of otherworldly dread that gets under your skin.

How It Stacks Up Against the Source Material

Now, if you’ve read the Strugatsky brothers’ Roadside Picnic, you might be scratching your head wondering where all the cool alien artifacts went. The novel is a gritty, action-packed tale about “stalkers” who illegally scavenge bizarre objects from the Zone to sell on the black market. It’s got invisible crushing forces, gravity traps, “mosquito mange,” and all sorts of wild anomalies that’ll turn you into meat paste if you’re not careful.

The book’s Zone is unquestionably alien, littered with incomprehensible artifacts like “empties” (containers of nothing), “black sprays” (which dissolve organic matter), and the legendary Golden Sphere that grants wishes. The stalkers are blue-collar criminals, not philosophers. They’re in it for the money, risking their lives to feed their families. The protagonist, Red Schuhart, is a hard-drinking roughneck whose daughter is slowly mutating due to his Zone exposure.

Tarkovsky took that premise and stripped it down to the bone. Gone are most of the overt supernatural elements. The film’s Zone is eerily mundane—just abandoned buildings and nature reclaiming civilization. No floating balls of light, no gravity-defying phenomena, no alien artifacts to smuggle out. The only explicitly paranormal moment comes at the very end when the Stalker’s daughter, nicknamed Monkey, moves glasses across a table with her mind while staring directly at us.

This minimalist approach might frustrate fans of the book, but I think it’s genius. By removing the flashy sci-fi elements, Tarkovsky forces us to focus on what really matters: the characters’ inner turmoil. The novel’s Red is a survivor driven by profit and desperation. The film’s Stalker, by contrast, is almost monk-like in his devotion to the Zone. He believes it offers redemption to those brave enough to seek it. He’s not in it for money—he charges barely enough to survive. For him, guiding people to the Room is a calling, maybe even a form of worship.

The Philosophy of Desire

The heart of Stalker lies in its exploration of human desire and self-deception. As our trio gets closer to the Room, the real journey becomes internal. The Writer, who initially claimed he wanted inspiration, reveals deeper insecurities about his relevance and mortality. The Professor’s noble scientific goals mask something more sinister—he’s brought a bomb to destroy the Room, fearing what would happen if the wrong person’s desires came true.

But here’s the kicker: the Room doesn’t grant what you wish for. It grants what you truly desire in your subconscious. The Stalker tells the story of Porcupine, his mentor, who entered the Room wishing for his brother’s resurrection but came out rich instead. The guilt drove him to suicide. This twist transforms the Room from a magical wish-granting device into a mirror that reflects your true self—and most people can’t handle what they see.

When the three men finally reach the Room’s threshold, none of them enter. They sit outside in the rain, paralyzed by the possibility of discovering their authentic selves. The Writer realizes he doesn’t want his talent restored—he wants to be told he’s a genius without having to prove it. The Professor can’t bring himself to destroy humanity’s last hope, even if that hope is dangerous. And the Stalker, the true believer, perhaps fears learning that his faith is misplaced.

Where the Film Stumbles

I’ll be honest—this movie isn’t for everyone. The pacing is glacial, with long takes that seem to stretch into eternity. There’s one sequence where we watch the three men sleep for what feels like ten minutes while the camera slowly pans across their faces. Another scene has them sitting in silence while water drips in the background. Tarkovsky believed cinema should unfold in real time, forcing viewers to experience duration itself. Noble idea, but man, it can be a slog.

The dialogue often veers into pretentious territory too. The Writer and Professor spend much of their screen time spouting philosophical monologues that sound more like thesis statements than actual conversation. At one point, the Writer launches into a speech about the nature of art and suffering that goes on for several minutes without interruption. I get that these characters represent different worldviews—art versus science, faith versus reason—but subtlety isn’t Tarkovsky’s strong suit here.

The film also suffers from some dated gender politics. The only significant female character is the Stalker’s wife, who exists mainly to suffer nobly and deliver a single monologue about the nature of love. Their daughter, Monkey, is more plot device than character, her telekinetic abilities serving as a heavy-handed metaphor for the next generation’s potential.

Why It Still Works

Despite these flaws, Stalker achieves something rare in cinema: it makes you feel the weight of existence. The Zone becomes a mirror for our own psychological landscapes, those treacherous inner territories where our true desires hide. Every careful step through the Zone’s dangers reflects our own navigation through life’s uncertainties.

The film’s power lies in its ambiguity. We never know if the Zone’s dangers are real or if the Stalker is delusional. Maybe the Room is just an empty chamber in an abandoned building. Maybe the whole thing is an elaborate metaphor for the Soviet system, or organized religion, or the human condition itself. Tarkovsky refuses to give easy answers, forcing viewers to grapple with the uncertainty.

There’s a moment near the end that encapsulates the film’s themes perfectly. The Stalker lies in shallow water, exhausted and defeated after his clients refuse to enter the Room. His wife appears, and they embrace in the mud while he weeps about humanity’s loss of faith. It’s raw, uncomfortable, and deeply moving. Here’s a man whose entire worldview has been shattered, yet he’ll return to the Zone because it’s all he knows.

The Legacy

Stalker has influenced countless films, from Lars von Trier’s Melancholia to Alex Garland’s Annihilation. The concept of the Zone has entered popular culture, inspiring everything from the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. video game series to philosophical discussions about liminal spaces. But more than its cultural impact, the film endures because it asks questions that remain relevant: What do we really want? Can we handle the truth about ourselves? Is faith possible in a world that seems increasingly meaningless?

Watching Stalker in today’s world hits different. We live in our own Zone now—a place where reality feels increasingly unstable, where invisible dangers lurk around every corner, where our deepest desires are reflected back at us through social media algorithms. The film’s meditation on faith, despair, and the search for meaning resonates even more strongly in our current moment of uncertainty.

The Verdict

Stalker frustrates me as much as it fascinates me. It’s slow, self-important, and demands patience I don’t always have. There are times when I want to shake Tarkovsky and tell him to get on with it. But it’s also one of the most profound meditations on human nature I’ve encountered in any medium. Where Roadside Picnic gave us a thrilling tale of survival in an alien-touched world, Tarkovsky delivered something harder to define—a spiritual journey that uses science fiction as a springboard into the depths of the soul.

I give it a solid thumbs up, with several caveats. Don’t watch this expecting Star Wars or even Solaris. Don’t watch it when you’re tired or distracted. Don’t expect clear answers or conventional narrative satisfaction. Come to it ready to wrestle with big questions and bigger silences. Bring patience and an open mind.

The Zone is waiting, but only you can decide if you’re ready to enter. And like the characters in the film, you might find that the real question isn’t whether you can reach your destination—it’s whether you have the courage to face what you’ll find there.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.