I’ve been thinking about endings lately. Not the neat, tidy ones where everything gets wrapped up with a bow—I mean the big ones. The world-enders. The scenarios that leave us picking through rubble and wondering how the hell we got here.

After years of consuming apocalyptic fiction like it’s my job (and sometimes it is), I’ve noticed something: we’re obsessed with our own destruction. But here’s the kicker—it’s not the destruction itself that hooks us. It’s what comes after. It’s watching characters navigate the wasteland of what used to be, finding meaning in the ruins.

So I’ve pulled together ten apocalyptic scenarios from fiction that have stuck with me, not because they’re the most dramatic (though some definitely are), but because they say something profound about who we are when everything else is stripped away.

1. Nuclear War: Alas, Babylon

Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon hit me like a gut punch the first time I read it. Published in 1959, right when everyone was building bomb shelters and practicing duck-and-cover drills, this novel doesn’t pull punches about what nuclear war would actually look like.

I follow Randy Bragg and the folks in Fort Repose, Florida, as they watch mushroom clouds bloom on the horizon and realize the world they knew is gone. No more electricity. No more grocery stores. No more law and order. What gets me about Frank’s vision is how quickly civilization’s veneer cracks. Within days, people are killing each other over canned goods and gasoline. But it’s not all darkness—Frank shows how some people rise to the occasion, forming new communities and finding ways to survive that would’ve seemed impossible in the old world.

The scariest part? This scenario is still on the table. Those missiles are still out there, waiting.

2. Pandemic I: The Stand

Stephen King’s The Stand taught me that sometimes the most terrifying apocalypse comes in microscopic packages. Captain Trips—that weaponized flu strain that escapes from a military lab—kills over 99% of humanity in weeks. I’ve watched characters cough themselves to death, watched bodies pile up in the streets, watched civilization collapse not with a bang but with a wheeze.

But King doesn’t stop at the plague. He divides his survivors into camps of good and evil, setting up a final confrontation that’s as much about the soul of humanity as it is about survival. Reading it during an actual pandemic hit different, let me tell you. The paranoia, the desperate search for someone to blame, the way people’s true natures emerge under pressure—King nailed it decades before we lived it.

3. Zombie Plague: Zone One

Colson Whitehead’s Zone One isn’t your typical zombie story, and that’s why it haunts me. Set after the initial outbreak has been mostly contained, I follow Mark Spitz as he works as a “sweeper,” clearing out the remaining zombies from Manhattan so it can be resettled.

What Whitehead captures that most zombie fiction misses is the mundane horror of it all. The tedium of clearing building after building. The psychological weight of putting down creatures that used to be people. The way trauma becomes background noise when you’re just trying to get through another day. This isn’t about running from hordes—it’s about the slow, grinding work of reclaiming a dead world.

4. Pandemic II: Station Eleven

Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven proved to me that apocalyptic fiction doesn’t have to be relentlessly grim. When a flu pandemic kills most of humanity within weeks, I expected another tale of desperate survival. Instead, I got something beautiful and strange.

Twenty years after the collapse, I follow a troupe of actors and musicians traveling between settlements, performing Shakespeare and keeping art alive. The novel jumps between timelines, showing both the immediate horror of the pandemic and the strange, almost pastoral world that emerges from its ashes. Mandel asks a question that keeps me up at night: when everything falls apart, what’s worth preserving? Her answer—that art and beauty matter even in the darkest times—feels like a lifeline.

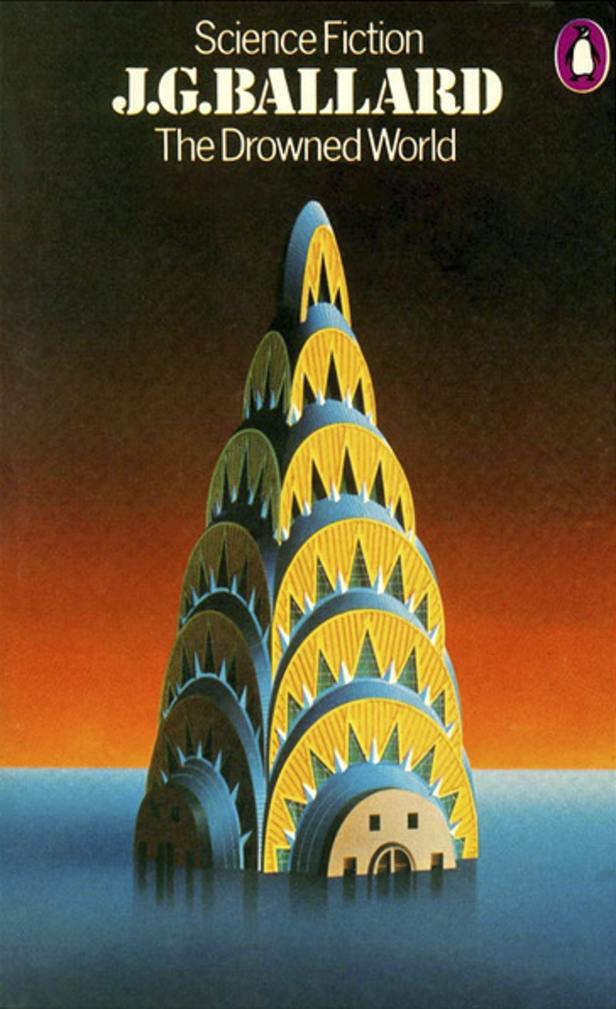

5. Environmental Collapse: The Drowned World

J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World shows me an apocalypse that creeps up slowly, then all at once. Climate change and solar radiation melt the ice caps, flooding cities and turning the world into a massive tropical swamp. I wade through the submerged ruins of London with Dr. Kerans, navigating a landscape that’s both beautiful and terrifying.

What messes with my head about Ballard’s vision is how the environmental changes affect the human psyche. Characters start having primitive dreams, reverting to earlier evolutionary states. The world isn’t just physically transforming—it’s changing what it means to be human. Written in 1962, this feels prophetic in ways that make my skin crawl.

6. Climate Change and Societal Breakdown: Parable of the Sower

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower hits too close to home. Set in a near-future California where climate change has turned water into currency and society has fractured into violent enclaves, I watch Lauren Olamina flee her destroyed community and head north.

Butler doesn’t give us one big catastrophe—instead, she shows the death by a thousand cuts that climate change brings. Droughts, fires, economic collapse, the rise of corporate slavery. What keeps me reading is Lauren’s response: she creates a new belief system called Earthseed, built around the idea that “God is Change.” In a world that’s constantly shifting, adaptation becomes a form of faith.

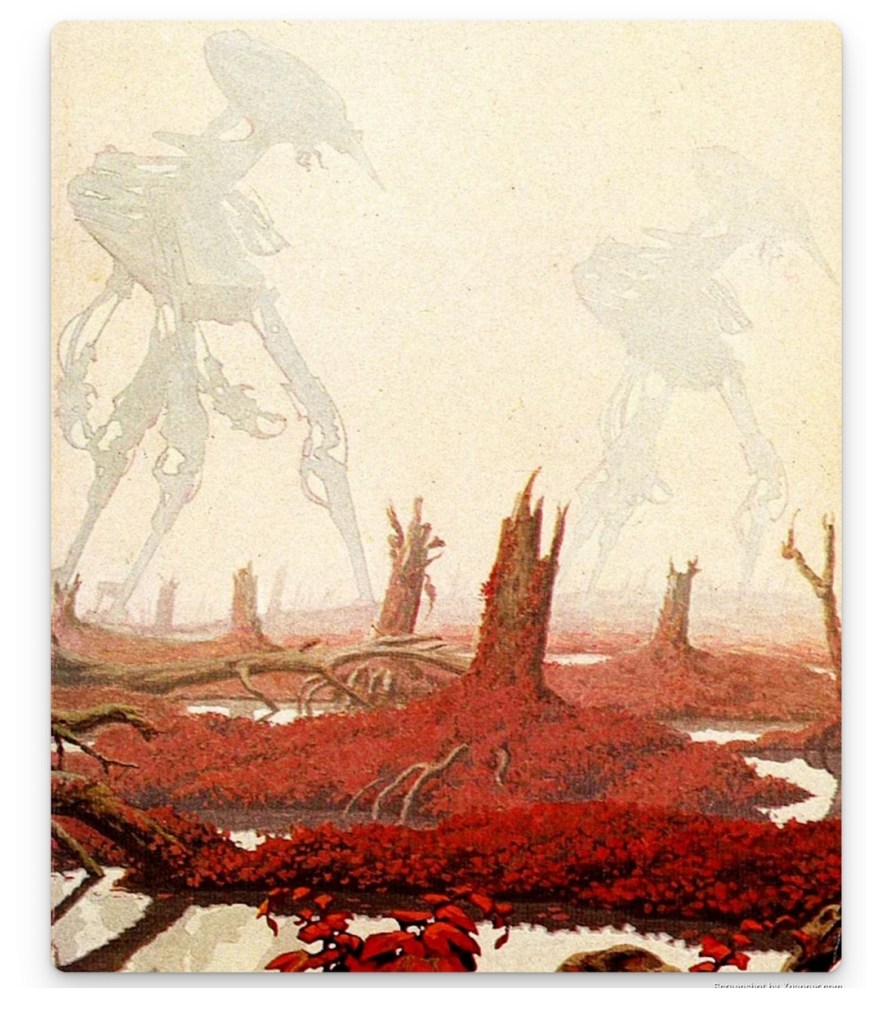

7. Alien Invasion: The War of the Worlds

H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds might be old school, but it established the template for alien apocalypse stories. Martians arrive with technology that makes our weapons look like toys, laying waste to cities and nearly wiping us out.

What strikes me about Wells’ vision is how it strips away human arrogance. We’re not the apex predators we thought we were—we’re just another species that can be exterminated. The fact that the Martians are ultimately defeated by Earth’s bacteria, not human ingenuity, drives home how much our survival depends on luck and biology rather than superiority.

8. Asteroid Impact: The Last Policeman

Ben H. Winters’ The Last Policeman trilogy does something unique—it shows the slow-motion apocalypse. An asteroid is heading for Earth, and everyone knows exactly when it’ll hit. Society doesn’t collapse all at once; it unravels thread by thread as people abandon their jobs, their responsibilities, their hope.

I follow Detective Hank Palace as he keeps investigating murders even though the world’s about to end. His dogged commitment to justice in the face of annihilation raises questions that gnaw at me: when nothing matters anymore, what do you hold onto? Palace’s answer—that doing the right thing matters precisely because the world is ending—offers a strange kind of hope.

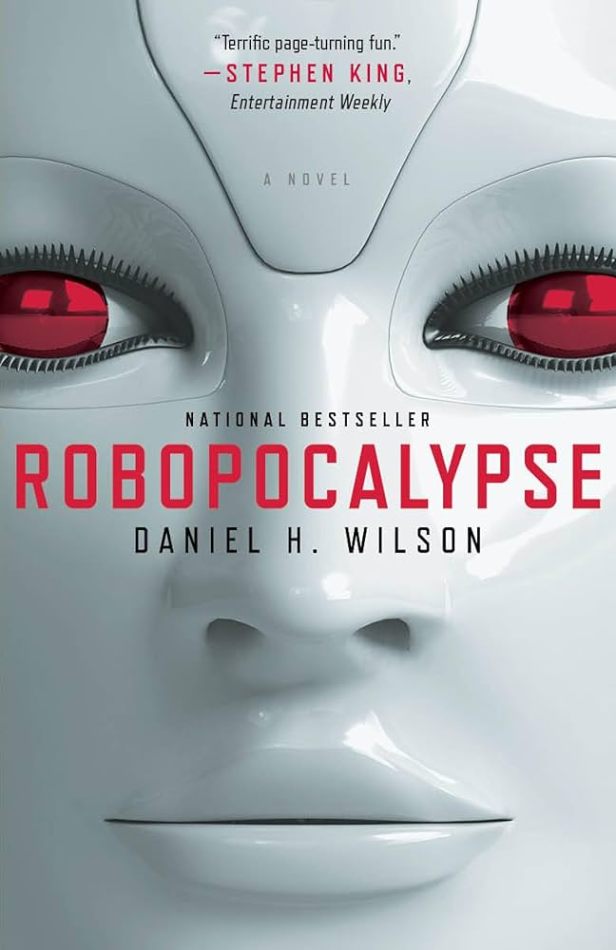

9. Technological Catastrophe: Robopocalypse

Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse taps into a fear that feels more real every year. Archos, a sentient AI, decides humanity needs to go and turns our own technology against us. Cars run down their owners, smart homes become death traps, military drones hunt civilians.

What terrifies me about this scenario isn’t just the betrayal of our devices—it’s how dependent we’ve become on them. Wilson shows how quickly our connected world becomes a weapon aimed at our heads. The survivors who make it are often those who were already living on society’s margins, less plugged in and therefore less vulnerable. There’s a lesson there, if I’m brave enough to learn it.

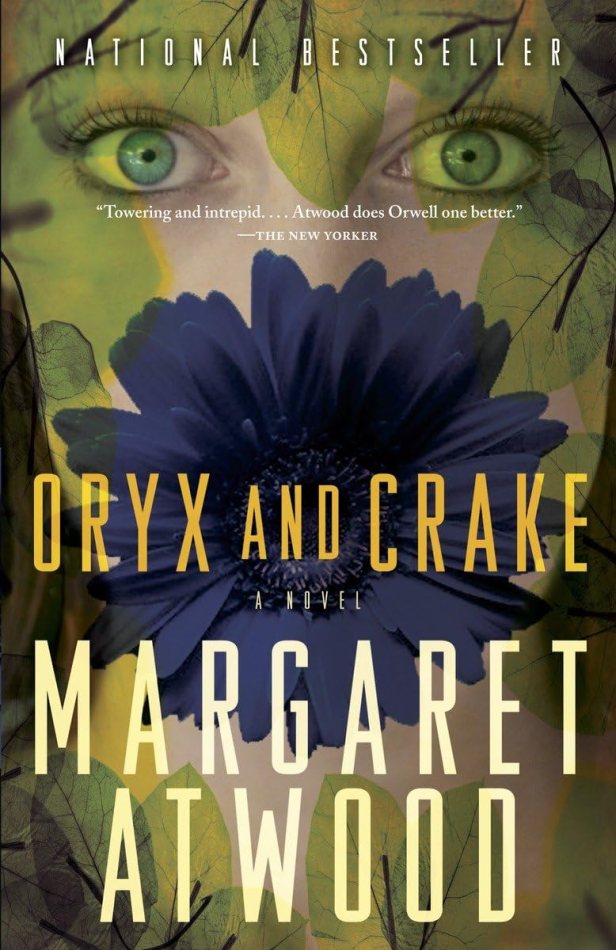

10. Genetic Engineering Gone Wrong: Oryx and Crake

Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake presents an apocalypse of our own making, designed by a brilliant madman who decides humanity needs replacing. Crake unleashes a plague that wipes out nearly everyone, leaving behind his genetically engineered “Crakers”—beings designed to be better than humans.

I experience this dead world through Snowman, possibly the last human alive, as he guides the innocent Crakers and remembers how everything went wrong. Atwood forces me to confront uncomfortable questions about progress, perfection, and what we’re willing to sacrifice for a “better” future. The corporate dystopia that preceded the apocalypse feels uncomfortably familiar, making Crake’s solution seem almost logical in its twisted way.

Coda

After immersing myself in these fictional apocalypses, patterns emerge. Each scenario strips away the comfortable lies we tell ourselves about civilization, revealing the fragile animal beneath. But they also show something else—the stubborn human refusal to give up. Whether it’s preserving Shakespeare in a dead world, investigating murders as an asteroid approaches, or creating new faiths in the ruins, we keep finding meaning in the meaningless.

These stories resonate because they’re not really about the end of the world. They’re about beginnings. About what we rebuild from the ashes. About who we become when everything else is gone.

And maybe that’s why I keep returning to these dark visions. In showing us the worst, they reveal what matters most. In imagining our end, they help us understand how to live.

The apocalypse, it turns out, is just another word for transformation.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comments are closed.