Welcome, Fear Planet denizens, to my review of Keith Roberts’ Pavane, one of those books that grabbed me by the throat and refused to let go.

Published in 1968, Pavane is a masterpiece of alternate history that reads like a fever dream of what England might have become if history had taken just one different turn. It’s not your typical “what if the Nazis won” alternate history—Roberts goes deeper, nastier, more personal. He imagines a world where the Catholic Church never lost its stranglehold on European civilization, where steam engines still chug through a landscape that feels both familiar and utterly alien.

The book hit me like a sledgehammer wrapped in styrofoam when I first picked it up ages ago. Roberts doesn’t just craft an alternate timeline; he creates a living, breathing world that feels more real than most contemporary fiction. Every page drips with the kind of atmospheric detail that makes your skin crawl and your heart race. This isn’t science fiction as escapism—this is science fiction as examination, a brutal autopsy of progress, power, and the price we pay for both.

The Plot: Six Measures of a Deadly Dance

Pavane unfolds like its namesake—a stately court dance performed in six deliberate movements. But there’s nothing courtly about Roberts’ vision. This is a dance of death, oppression, and the slow burn of rebellion that spans nearly a century of alternate English history.

The Point of No Return

Everything changes in 1588. Queen Elizabeth I takes an assassin’s bullet just as the Spanish Armada approaches English shores. Without the Virgin Queen to rally Protestant England, the country collapses into civil war. The Spanish land unopposed, crush the Reformation across Europe, and hand absolute power to the Catholic Church. By the 20th century, the Pope rules not just spiritually but temporally, controlling every aspect of life from Londinium to the smallest village.

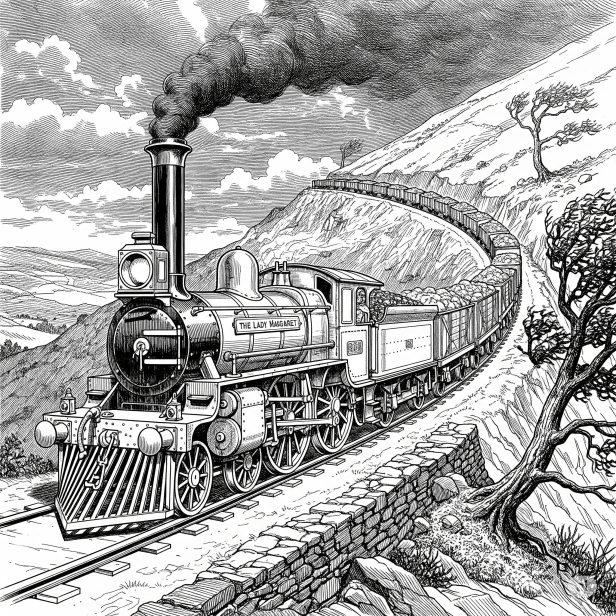

Measure One: “The Lady Margaret” (Late 1960s)

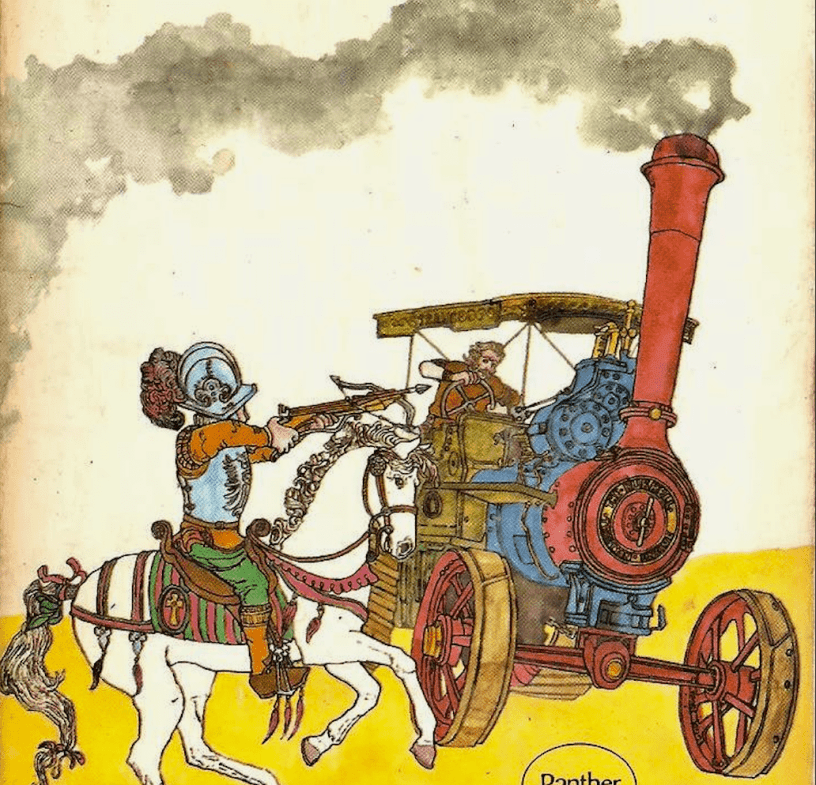

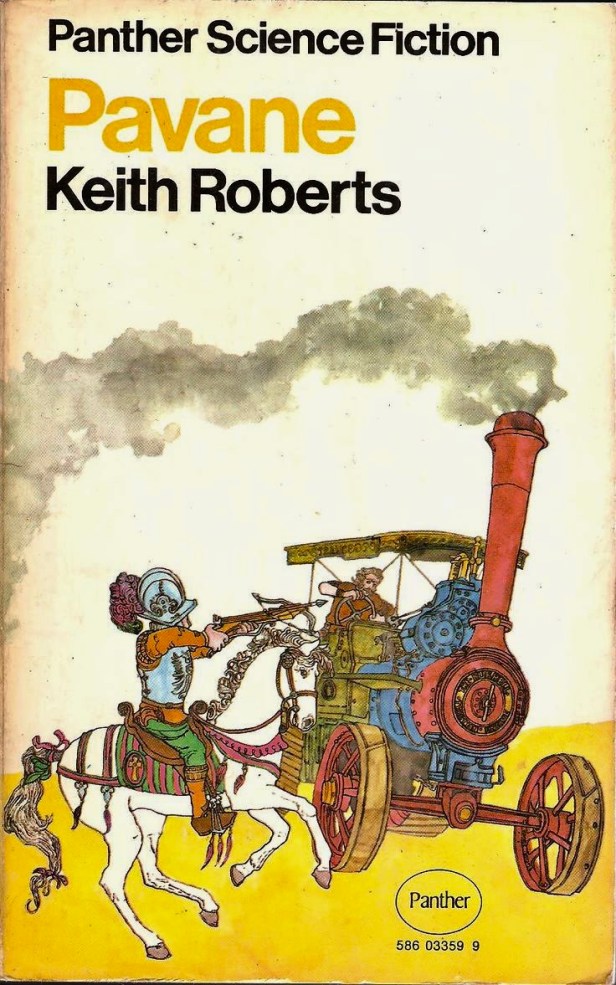

Roberts throws us headfirst into this nightmare with Jesse Strange, a steam haulier who pilots massive road trains through England’s dangerous countryside. Picture Mad Max crossed with Victorian steam technology, and you’re getting close. Jesse operates the “Lady Margaret,” a steam locomotive that hauls freight wagons across roads instead of rails, navigating a landscape where wolves still hunt and bandits prey on travelers.

Jesse’s final run from Durnovaria to Poole becomes a journey through hell when his old friend turns bandit and tries to rob the convoy. The confrontation ends in violence and death—Jesse uses explosive charges to eliminate the threat, but the victory feels hollow. His romantic pursuit of Margaret, the woman who shares his locomotive’s name, ends in gentle rejection. Jesse is left alone with only his beloved machine for companionship, a perfect metaphor for this world’s isolation and technological stagnation.

Measure Two: “The Signaller” (1970s)

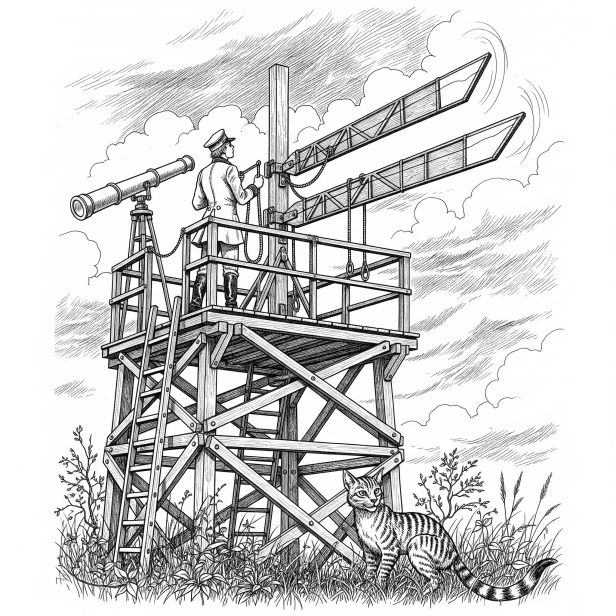

The story shifts to Rafe Bigland, a young apprentice working in England’s semaphore communication network. These massive wooden towers with their clattering mechanical arms represent the cutting edge of Church-approved technology. Electrical communication remains forbidden, so messages travel through an elaborate system of visual signals that dot the countryside like skeletal monuments to controlled progress.

Rafe’s story becomes a truncated biography when a wildcat attack cuts his life short. Through his eyes, we see how the Church micromanages every aspect of technological development through endless papal bulls that dictate what fuels can be used, how efficient engines can be, and what forms of communication are permitted. It’s bureaucratic oppression disguised as divine mandate.

Measure Three: “Brother John” (1980s)

Roberts turns his lens inward to examine the Church itself through Brother John, a monk whose faith crumbles as he witnesses the Inquisition’s brutality. The story chronicles John’s growing horror at the Church’s methods and his eventual rebellion against the institution he once served.

But Roberts doesn’t make this a simple tale of good versus evil. Even as John rebels, he begs his followers not to hate the Church or Christ. The Bishop of Londinium privately acknowledges the Church’s failings in handling John’s situation. This nuanced approach to religious themes shows Roberts at his most sophisticated—he’s not interested in cheap shots at organized religion, but in exploring the complex relationship between power, faith, and moral compromise.

Measure Four: “Lords and Ladies” (1990s)

The narrative returns to the Strange family through Margaret, Jesse’s niece, who has inherited wealth from Jesse’s successful expansion of the haulage business. The story opens with Jesse’s peaceful death, witnessed by Margaret, creating a poignant connection between the measures.

Margaret becomes a desirable marriage prospect for Lord Robert of Wessex, both for her money and her lack of male heirs. But supernatural elements creep into the story as Margaret experiences visions of pagan spirits and encounters with the mysterious “People of the Hills”—fairy folk who speak of cycles and warn about Mother Church. These mystical encounters hint at deeper forces at work beneath the surface of Roberts’ alternate world.

Measure Five: “The White Boat” (Early 2000s)

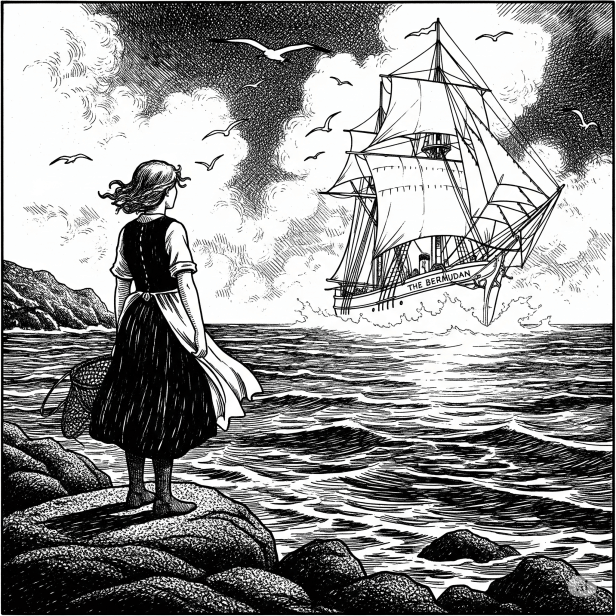

This story follows a simple fishergirl who becomes obsessed with a mysterious white vessel that visits her coastal cove. The boat, called The Bermudan, is actually part of a smuggling operation bringing prohibited technologies into England from abroad.

The fishergirl joins the crew but remains seasick and miserable throughout their Mediterranean voyages, taking no active part in their trade in forbidden knowledge. When the boat returns to England, she escapes but later betrays The Bermudan to Church authorities out of resentment. However, she ultimately repents and helps save the boat from capture. It’s a story about complicity, betrayal, and the small acts of conscience that can tip the balance between oppression and freedom.

Measure Six: “Corfe Gate” (Early 21st Century)

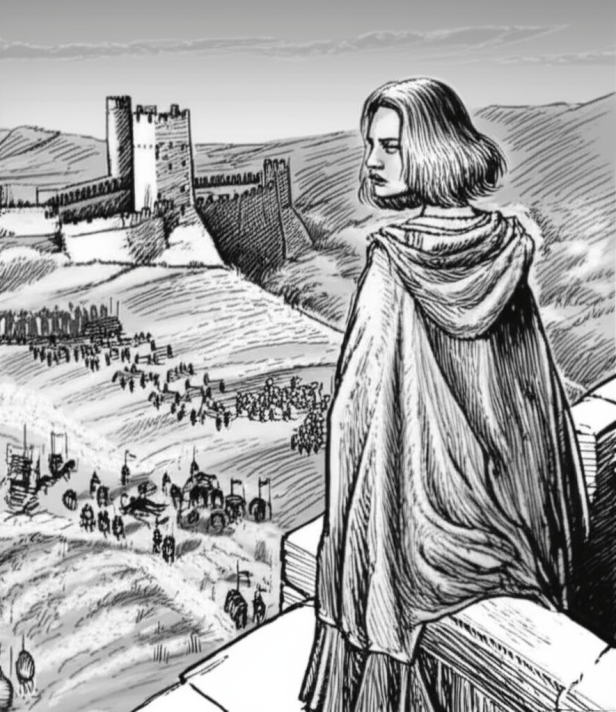

The climactic story centers on Lady Eleanor, daughter of Sir Robert and Margaret Strange, now ruling at Corfe Castle. Eleanor embodies a vigorous, practical-minded England growing increasingly restless under centuries of papal control.

The crisis erupts during a famine year when the Church still demands its full tribute despite widespread starvation. Eleanor refuses to let her subjects starve for Rome’s sake, offering manufactured goods instead or promising to make up the shortfall later. The Church rejects her proposal and sends soldiers to remove her from power.

Eleanor responds to the papal summons “with a whiff of grapeshot,” beginning a siege that closely parallels the historical Civil War sieges of Corfe Castle. Her rebellion sparks an insurrection across England as the fundamental question of sovereignty—king or pope—is raised once again.

Like her historical inspiration, Lady Mary Bankes, Eleanor’s personal triumph is bittersweet. While her rebellion shifts power away from the Church and leads to the emergence of technologies that had been developed in secret, Eleanor herself doesn’t personally triumph. She surrenders the castle to the king’s forces, Corfe is demolished, and Eleanor vanishes into history’s shadows.

The Coda: Cosmic Revelation

Set further in the 21st century in a thoroughly modern England with flying cars and nuclear fusion, the coda delivers a stunning revelation that transforms everything we thought we knew about Roberts’ world.

John, son of Eleanor and the mysterious Sir John Faulkner (revealed to be one of the Fae), visits Corfe’s ruins and reads his father’s letter explaining the cosmic truth. The world of Pavane isn’t actually alternate history—it’s the second iteration of our own world, which ended in nuclear holocaust and human extinction.

When the cycle began again, the fairy folk told the 16th-century Catholic Church about humanity’s future self-destruction, hoping that delaying technological progress might prevent the same catastrophic path. As Sir John’s letter explains: “The Church knew there was no halting Progress; but slowing it, slowing it even by half a century, giving man time to reach a little higher towards true Reason; that was the gift she gave this world.”

The Church’s oppression was motivated by knowledge of humanity’s capacity for even greater horrors. There was no Belsen, no Buchenwald, no Passchendaele in this world—the price of preventing industrial-scale atrocity was centuries of controlled stagnation.

My Review: A Near-Perfect Masterpiece

Pavane isn’t just one of the finest alternate history novels ever written—it’s one of the most profound meditations on progress, power, and human nature that science fiction has produced. Roberts crafted something that transcends genre boundaries, creating a work that functions simultaneously as alternate history, fantasy, and philosophical inquiry.

Literary Craftsmanship That Demands Respect

Roberts’ prose style matches the stately dance of his title—measured, deliberate, lyrical without being flowery. He doesn’t waste words, but every sentence carries weight. The atmospheric descriptions feel lived-in rather than constructed, creating a world that exists in your peripheral vision even when you’re not reading. This is writing that understands the power of restraint, building tension through accumulation of detail rather than dramatic flourishes.

The book’s structure as a “fix-up” novel of interconnected stories works brilliantly. Each measure functions as a complete story while contributing to the larger narrative arc. Roberts uses this structure to show how individual actions ripple through generations, how personal choices become historical forces. The Strange family line provides continuity while allowing Roberts to explore different aspects of his world through fresh perspectives.

Thematic Complexity That Refuses Easy Answers

What sets Pavane apart from other alternate histories is its refusal to provide simple moral judgments. Roberts doesn’t present the Church as pure evil or the rebels as pure good. Instead, he creates a complex moral landscape where every choice comes with costs, where progress and stagnation both exact their prices.

The revelation in the coda transforms the entire novel from alternate history into something more philosophically ambitious. Roberts asks whether humanity is capable of learning from its mistakes, whether knowledge of future catastrophe justifies present oppression. The Church’s actions, horrific as they are, prevent even greater horrors—industrial warfare, genocide, nuclear annihilation.

This moral ambiguity extends to the characters. Jesse Strange is neither hero nor victim but a man trying to make his way in a world not of his choosing. Brother John rebels against Church brutality but doesn’t reject faith entirely. Lady Eleanor fights for her people’s survival but pays a personal price for her rebellion. These are human beings caught in historical forces beyond their control, making choices based on limited information and competing loyalties.

Atmospheric Worldbuilding That Haunts You

Roberts creates a world that feels both alien and familiar, a 20th-century England that could have existed if history had taken a different turn. The details accumulate to create an atmosphere of controlled decay—steam engines that could be more efficient but aren’t allowed to be, communication networks that work but remain deliberately primitive, a landscape dotted with medieval structures alongside industrial machinery.

The supernatural elements add mythological depth without overwhelming the historical framework. The fairy folk represent connection to the land and ancient wisdom, forces that exist outside human institutions but influence them nonetheless. Their presence suggests that there are powers older than Church or State, cycles larger than human history.

Influence and Legacy

Pavane influenced the development of steampunk aesthetics decades before the genre was formally named, presenting steam technology in romanticized yet realistic detail. But its influence goes beyond genre fiction into discussions of technological progress, religious authority, and the nature of historical change.

The book’s relative obscurity compared to American alternate histories may stem from its British setting, complex structure, and Roberts’ difficult personality, which led to disputes with publishers throughout his career. But this obscurity is also part of its appeal—Pavane remains a discovery, a book that rewards readers willing to engage with its contemplative pace and profound themes.

A Dance That Ends Too Soon

If I have any criticism of Pavane, it’s that I want more. Roberts created a world so rich, so detailed, so haunting that six measures feel insufficient. But perhaps that’s the point—like the dance that gives the book its title, Pavane follows a precise form that doesn’t outstay its welcome. Roberts knew when to end the dance, leaving readers wanting more rather than overstaying his welcome.

The controversial coda divides readers, and I understand why. Some find it jarring, a science fictional intrusion into what had been a work of historical speculation. But for me, it transforms the entire novel into something larger, a meditation on cycles of history and the price of knowledge. It’s the kind of bold narrative choice that separates masterworks from merely good books.

Pavane stands as proof that science fiction at its best doesn’t just imagine different worlds—it illuminates our own. Roberts created a dark mirror of our history that reflects our fears about progress, power, and the choices we make as a species. It’s a book that stays with you long after you finish reading, a dance that echoes in your mind whenever you consider the price of the world we’ve built.

In an era of formulaic science fiction and predictable alternate histories, Pavane remains genuinely shocking, genuinely moving, genuinely important. It’s a book that trusts its readers to grapple with complex themes and moral ambiguity, a work that rewards careful attention and repeated reading. For anyone serious about science fiction as literature, Pavane isn’t just recommended—it’s essential.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.