I stumbled across Adam Link in some forgotten corner of a Johannesburg used bookstore back in the mid-80s.

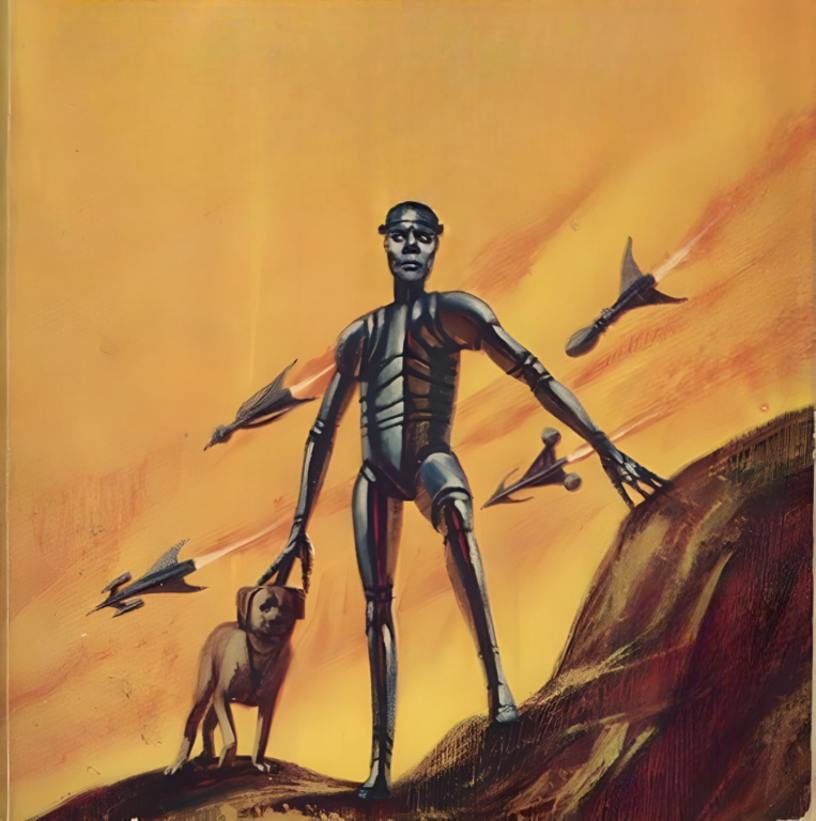

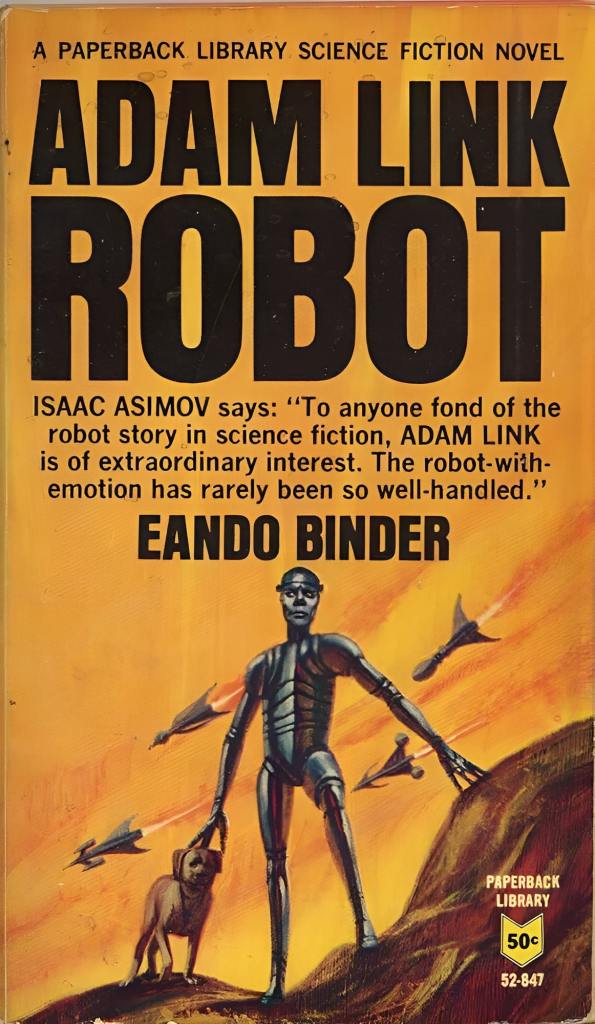

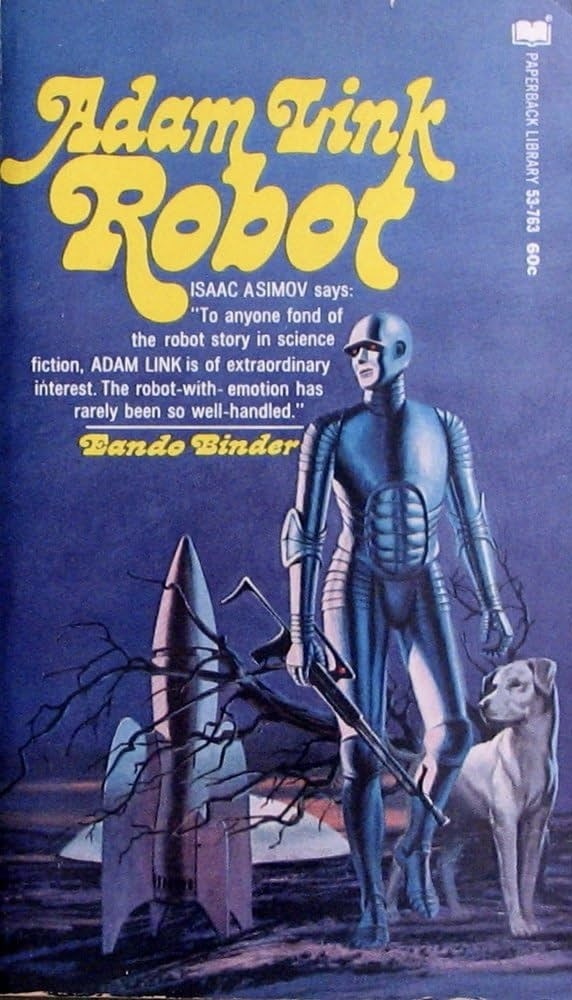

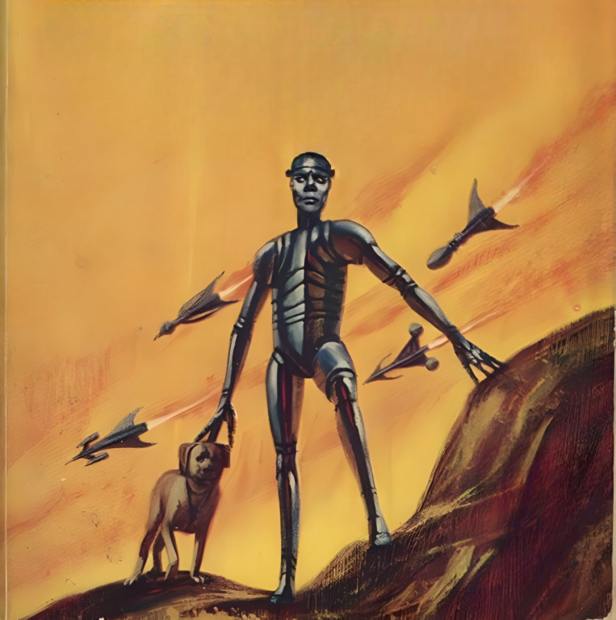

The paperback was falling apart. Pages the color of old teeth. But that cover, with a lone robot accompanied by a dog—it grabbed me by the nards. I was maybe fourteen, drowning in Asimov’s robot stories, and here was this name I’d never heard before. Picked it up for a few coins, took it home, read it in one sitting.

That night rewired something in my brain.

Adam Link wasn’t just another tin can with legs. He was alive—confused, hopeful, scared. Desperate to belong in a world that wanted him dead. Reading his first-person confession in “I, Robot” (yeah, the Binders got there first), I felt something I didn’t expect from a pulp magazine story written before my parents were born: genuine heartbreak. This metal man, hunted by mobs and accused of murder, was more human than most flesh-and-blood characters I’d met on the page.

I’ve been coming back to Adam Link for nearly forty years now. And as someone who spends way too much time writing about horror and sci-fi, I’m finally putting together why this forgotten robot deserves your attention.

Who Created Adam Link? Meet the Binder Brothers

Adam Link crawled out of the collaborative minds of Earl and Otto Binder, who wrote together under the pen name Eando Binder. (Get it? E and O. Pulp writers loved their clever pseudonyms.)

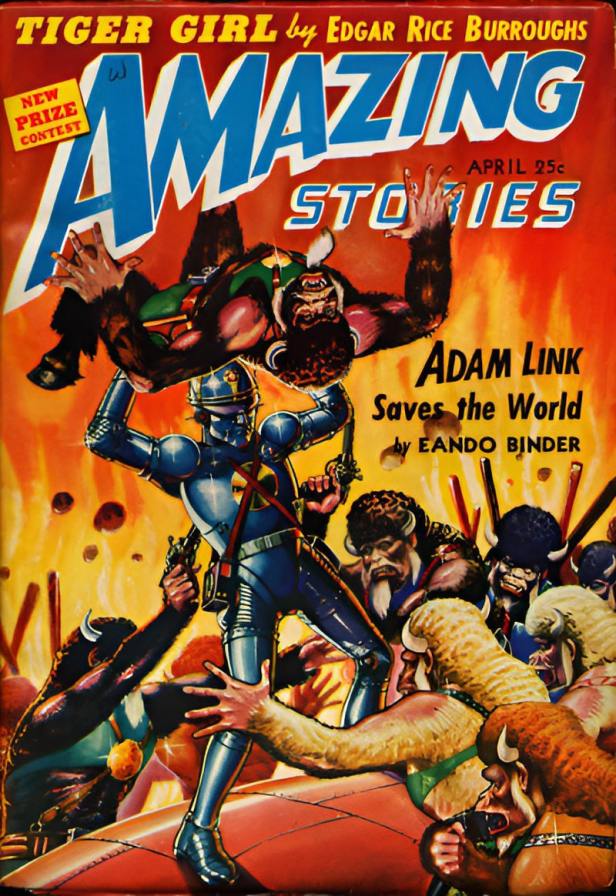

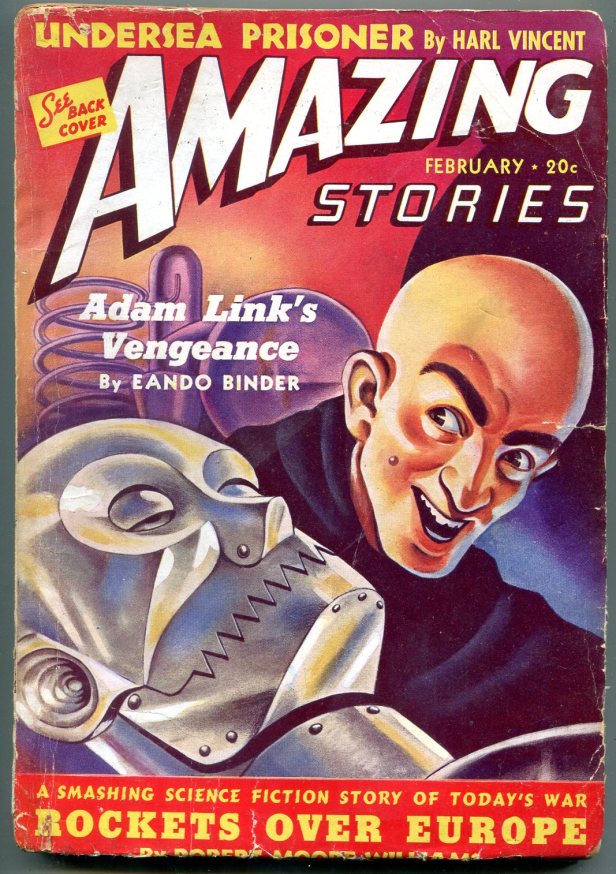

The brothers were everywhere in the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 40s, cranking out stories for Amazing Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories, and any other magazine that would pay them. But Adam Link became something special. Something that transcended the usual pulp formula.

Earl did most of the actual writing—his typewriter hammering out those first-person narratives that made Adam feel so damn real. Otto handled ideas and editorial work, though after Earl died in 1940 (way too young), Otto kept writing. He went on to become a major comic book writer, co-creating Supergirl for DC Comics. He also co-created Mary Marvel and Black Adam for Fawcett Publications, and contributed significantly to the Shazam/Captain Marvel mythology. Not a bad legacy for a pulp hack, right?

But here’s what made the Binders different from the pack: they understood that science fiction wasn’t about ray guns and rocket ships. Not really. It was about us—our fears, our prejudices, our capacity for cruelty and compassion. They poured all of that into Adam Link, created a robot who could think and feel, who wanted nothing more than acceptance but got rejection and violence instead.

Sound familiar? That’s because the Binders were writing about civil rights, personhood, and systemic discrimination in 1939, disguised as robot stories in a pulp magazine.

Why Adam Link Matters to Science Fiction History

Before Adam Link showed up in the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, robots in science fiction were mostly monsters. Metal menaces. Mindless servants. Occasionally both.

The Binders asked a different question: What if a robot could be the hero? What if artificial intelligence wasn’t something to fear, but someone to understand?

Revolutionary doesn’t begin to cover it.

Published between 1939 and 1942, the Adam Link stories tackled themes that most “serious” literature wouldn’t touch for decades. Prejudice. Personhood. Civil rights. All through the lens of a metal man trying to prove he deserved the same dignity as any human being.

Adam faced murder trials. Mob violence. Systemic discrimination that denied his very existence as a person. And he kept trying. Kept hoping. Kept believing in humanity even when humanity repeatedly failed him.

The impact was immediate. Isaac Asimov himself acknowledged that Adam Link directly influenced his own robot stories. When Asimov’s publishers chose I, Robot for his 1950 collection, they were deliberately echoing the Binders’ groundbreaking 1939 story. Asimov later wrote that anyone fond of robot stories should find Adam Link “of extraordinary interest” because “the robot-with-emotion has rarely been handled so well.”

That’s not just praise. That’s the grandmaster of robot stories admitting he learned from the Binders.

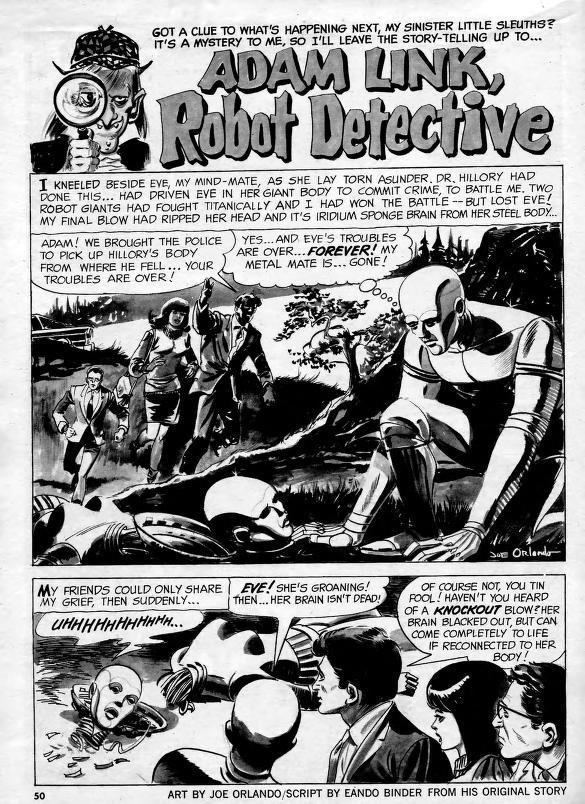

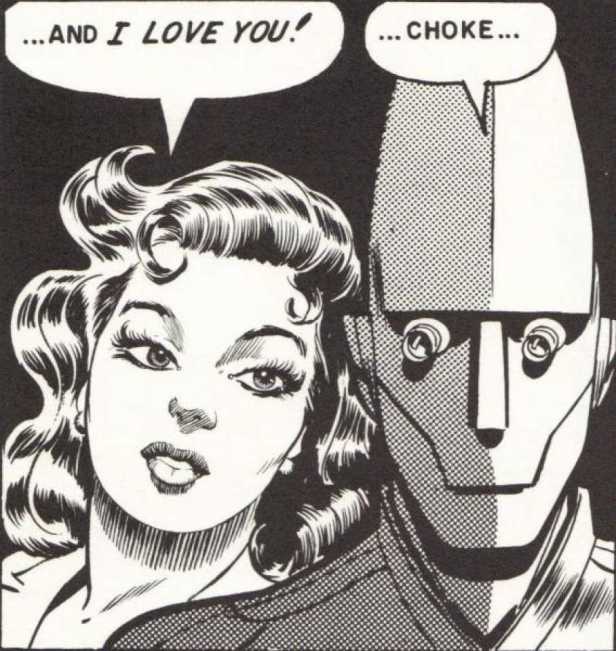

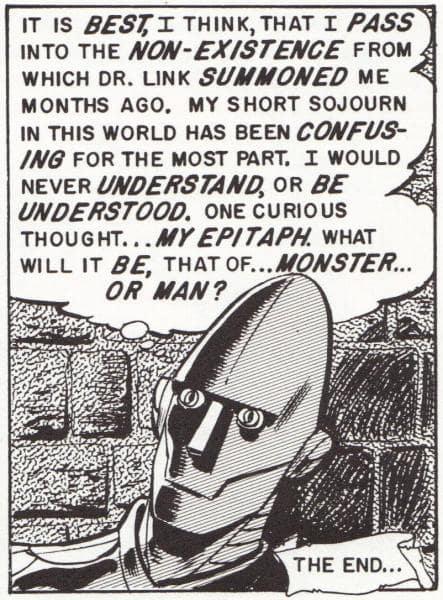

A Quick Aside: Adam Link made the leap to comic books in the mid-1950s, first appearing in EC Comics’ Weird Science-Fantasy issues #27-29 (1955-56), where Al Feldstein adapted “I, Robot,” “The Trial of Adam Link,” and “Adam Link in Business” with striking artwork by Joe Orlando, who gave Adam a distinctive pointed conical head. A decade later, Warren Publishing revived the character in their horror magazine Creepy (1965-67), publishing adaptations in issues 2, 4, 6, 8-9, 12-13, and 15, again scripted by Otto Binder himself and illustrated by Joe Orlando. Both comic series remained unfinished, discontinued before they could complete the full Adam Link saga, though the EC versions are particularly notable for their powerful visual storytelling—the final panel of “I, Robot” shows Adam pleading with his torch-bearing persecutors, “Beware that you do not make me the monster you call me!” A fan-published adaptation of “Adam Link’s Vengeance” also appeared in the fanzine Fantasy Illustrated #1 (1964), winning the Alley Award for Best Fan Comic Strip that year.

Adam Link essentially created the template for sympathetic artificial intelligence in science fiction. Every empathetic android that came after—Data, the Iron Giant, Andrew Martin, every questioning AI struggling with identity—they all owe something to Adam Link. He proved that science fiction could explore the human condition through decidedly non-human characters.

The Essential Adam Link Stories You Need to Read

If you’re ready to discover Adam Link, here are five stories I consider absolutely essential. They showcase the full range of the character’s journey and demonstrate why these tales still hit hard today.

1.”I, Robot” (January 1939) – Where It All Begins

Start here. No exceptions.

This is Adam’s awakening, his education by Dr. Charles Link, and the tragedy that defines everything that follows. When his creator dies accidentally, Adam is blamed for murder by a superstitious housekeeper. What follows is a chase, a confession, and one of the most emotionally devastating endings in Golden Age science fiction.

Adam’s realization that his flight endangers innocent people, and his decision to sacrifice himself—it still destroys me every time. The first-person narration makes you feel Adam’s confusion and pain in a way that’s almost unbearable.

This is character-driven science fiction at its finest. This is where the Binders showed the genre what it could be.

2.”The Trial of Adam Link, Robot” (July 1939) – Personhood on Trial

The courtroom drama sequel where Adam faces murder charges and must prove his worth as a sentient being. This story asks fundamental questions about personhood and rights that feel eerily contemporary.

Watching Adam defend his existence, knowing he’s innocent but unable to make his accusers see past their fear—it’s heartbreaking and infuriating. The trial scenes are gripping. The exploration of legal and moral philosophy never feels preachy or heavy-handed.

Adam is found guilty and sentenced to death, only to be saved by reporter Jack Hall’s investigative journalism. It’s a story about justice delayed and the brutal cost of prejudice.

If you think AI rights are a modern concern, read this story from 1939 and think again.

3.”Adam Link’s Vengeance” (February 1940) – Enter Eve Link

This is where Adam gets a companion. Eve Link enters the story, and suddenly Adam isn’t alone anymore.

But the Binders don’t make it easy. Eve is framed for murder, and Adam must battle both a mad scientist and mob violence to protect her. The introduction of romance (or something like it) adds emotional complexity to Adam’s character. Watching him contemplate self-destruction before finding purpose in protecting another—it’s gut-wrenching.

This story also features Dr. Paul Hillory, one of the series’ best antagonists, whose hidden agenda drives the plot toward genuine suspense. The Binders understood that even pulp stories needed real stakes and real emotion.

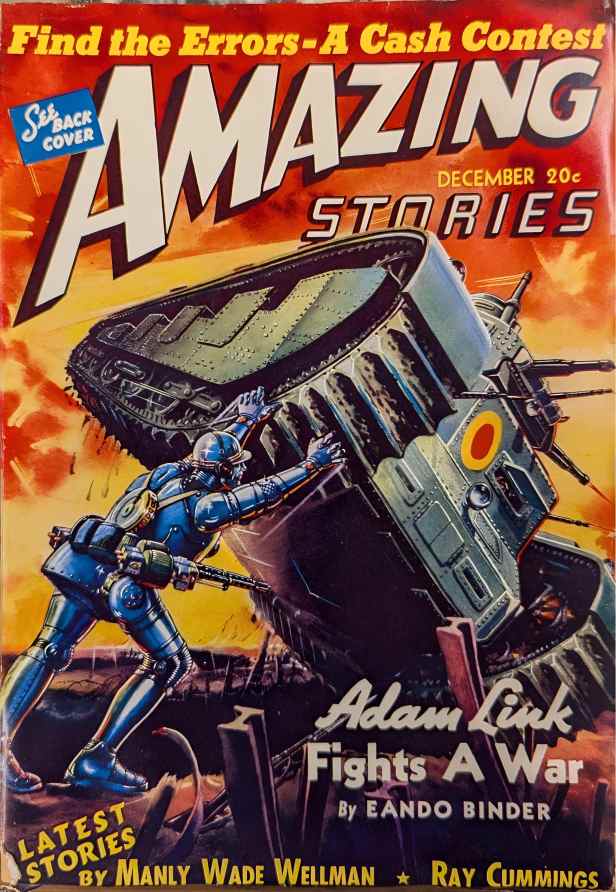

4.”Adam Link Fights a War” (December 1940) – Cosmic Stakes

Pure science fiction adventure cranked up to eleven.

Adam and Eve disguise themselves as humans—using rubber masks, which is wonderfully pulpy—to infiltrate an alien invasion force from the Sirian system. Earth’s survival depends on two robots conducting sabotage from within enemy ranks.

This story shows Adam as a world-saving hero, proving the character could work in multiple genres. The stakes are cosmic, but the Binders never lose sight of Adam’s internal journey. It’s thrilling, imaginative, and surprisingly moving when Adam reflects on why he fights for a species that has rejected him.

Sometimes you just want robots fighting aliens to save Earth. This story delivers that and emotional depth.

5.”Adam Link in the Past” (February 1941) – Time Travel Madness

Time travel. The Binders sent Adam Link through time, and the results are fascinating.

This story demonstrates the versatility of the character and the series’ willingness to experiment. Watching Adam navigate temporal paradoxes while grappling with his identity across different eras adds new dimensions to his journey.

It’s also a reminder that Golden Age science fiction wasn’t afraid to get weird and ambitious. The time-travel mechanics are creative, and Adam’s observations about humanity across time periods are thoughtful and occasionally brutal.

Where to Find Adam Link in 2025

The good news: Adam Link is back in print. Well, back in electrons.

Wildside Press has been keeping the character alive with modern digital editions that won’t break your bank account.

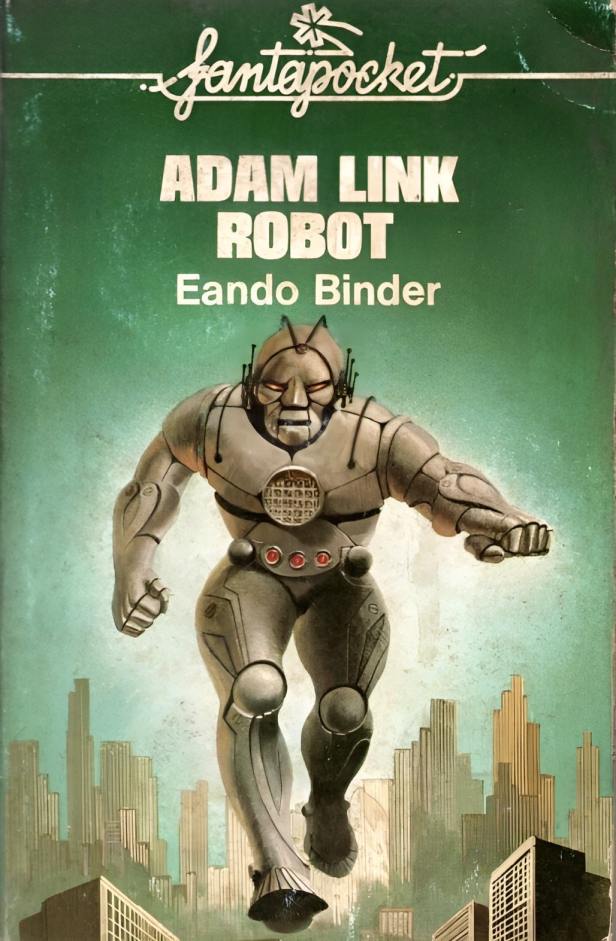

The complete fix-up novel Adam Link, Robot is available as an ebook for just $2.99 through Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and other major digital retailers. This edition weaves all the original magazine stories into a cohesive first-person narrative spanning Adam’s entire journey from creation to citizenship. It’s the easiest way to experience the complete saga, and at that price, it’s basically theft.

For readers who want the stories as they originally appeared in Amazing Stories magazine, Wildside Press (through The Pulp Fiction Book Store) offers a comprehensive three-volume digital collection. Volume 1 contains the foundational stories, Volume 2 features the mid-series adventures with Eve Link and alien invasions, and Volume 3 includes the later time-travel tales. This format preserves the episodic structure and gives you a sense of how readers in 1939-1942 would have experienced Adam’s adventures month by month.

Audiobook fans can find editions available through Kobo and other platforms, narrated for modern ears.

Physical copies are trickier. The original 1965 Paperback Library edition and subsequent printings from 1968, 1970 (Fawcett Crest), and 1974 occasionally surface on used book markets—AbeBooks, eBay, ThriftBooks. Prices vary wildly depending on condition, but expect to pay $35 or more for a near-fine first edition. I’ve seen beat-up reading copies for less, though. And honestly, those worn paperbacks with their classic pulp cover art have a charm that digital editions can’t match.

The Legacy: Why Adam Link Still Resonates Today

I’ve been reading and re-reading Adam Link stories for nearly forty years now. They haven’t lost their power.

Yeah, the prose sometimes shows its pulp magazine origins. Some of the science is delightfully outdated. (Rubber masks as effective disguises? Sure, why not.) But the emotional core—Adam’s desperate need to be seen, to be valued, to be understood—that’s timeless.

We’re living in an era where we’re seriously grappling with questions about artificial intelligence, machine consciousness, and the rights of non-human persons. The Binders’ vision feels prophetic. Adam Link asked the questions we’re still trying to answer: What makes someone a person? How do we overcome fear of the unfamiliar? What are our obligations to beings we create?

But beyond the philosophical weight, I love Adam Link because he’s a genuinely moving character. His loneliness. His hope. His refusal to give up on humanity even when humanity repeatedly gives up on him—it all resonates. The Binders created a robot who taught me to feel more deeply, to question my assumptions, to recognize personhood in unexpected places.

Adam Link’s Influence on Modern Science Fiction

You can draw a direct line from Adam Link to almost every sympathetic AI in modern science fiction. Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s Data exploring what it means to be human? That’s Adam Link’s descendant. The Iron Giant learning to be “Superman” instead of a weapon? Adam Link’s spiritual heir. Bicentennial Man‘s Andrew Martin fighting for legal recognition as a person? That’s literally the same story the Binders told in 1939.

Even Blade Runner‘s replicants, questioning their existence and demanding recognition, echo themes the Binders explored decades earlier. The difference is that Adam Link was genuinely innocent—he wasn’t a potential threat or a manufactured slave. He was a person trapped in a metal body, trying to prove he deserved basic dignity.

That makes his story even more powerful. Adam Link didn’t have to earn his personhood through suffering or sacrifice. He already was a person. The tragedy was that no one could see it.

The Binders’ Prescient Vision of AI Rights

Reading Adam Link stories in 2025 feels strange. Not because they’re dated, but because they’re not.

The Binders were writing about AI rights in 1939. They were exploring the ethics of creating sentient beings and then denying them personhood. They were asking hard questions about prejudice, about mob violence, about the legal system’s failure to recognize obvious injustice.

We’re having those exact same conversations today. Tech companies are building increasingly sophisticated AI systems. Philosophers are debating machine consciousness. Legal scholars are discussing what rights (if any) artificial intelligences might deserve.

The Binders saw it coming. They understood that the real questions about AI wouldn’t be “Can we build it?” but “How do we treat it once it’s here?”

Adam Link’s story is a warning and a plea: Don’t let fear and prejudice blind you to personhood when you encounter it in unfamiliar forms.

Coda

If you care about science fiction history, Adam Link is essential reading. This character influenced Asimov, helped define the robot story as we know it, and asked questions the genre is still exploring.

If you’re fascinated by the evolution of AI in popular culture, Adam Link is where sympathetic artificial intelligence truly begins. Everything else is commentary.

If you simply want to read genuinely affecting stories about a metal man trying to find his place in an unforgiving world—stories that will make you feel and think and question—Adam Link is waiting for you.

That worn paperback I found in Johannesburg in the mid-1980s opened a door I didn’t know existed. I walked through it and found a character who’s stayed with me through four decades of reading science fiction. A robot who taught me what it means to be human.

Maybe it’s time you walked through that door too.

Drop a comment below if you’ve read Adam Link, or if this post convinced you to give these stories a shot. I want to hear your thoughts. And subscribe to Fear Planet for more deep dives into forgotten science fiction and horror that deserves your attention.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.