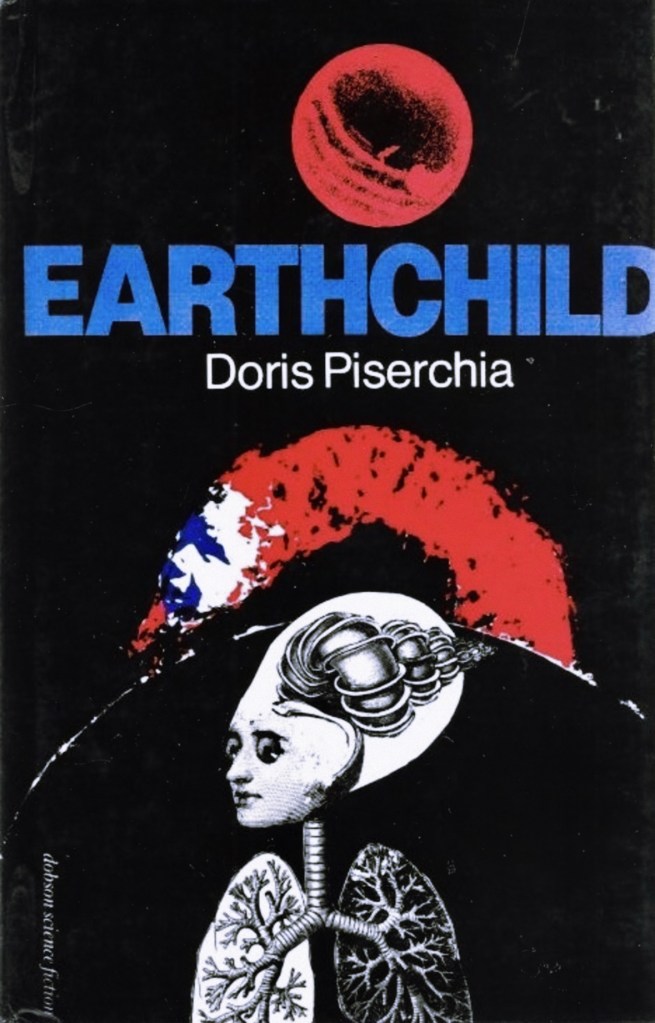

It’s a damn shame that I never even heard of Doris Piserchia until recently, because this woman was writing some of the most unique, bizarre, and unapologetically weird science fiction of the 1970s. It seems to me that, while everyone was reading Asimov and Clarke, Piserchia was over in the corner crafting fever-dream narratives about sentient oceans and rebellious teenage girls battling god-like ecologies. Earthchild (1977) is peak Piserchia: a psychedelic coming-of-age story wrapped in biological horror and wrapped again in “dying earth” mythology. It’s not perfect, but it’s unforgettable.

Who Was Doris Piserchia?

Doris Piserchia (1928–2021) was one of those writers who deserved more recognition than she got. Born in Fairmont, West Virginia during the Depression, she grew up poor, playing in forests and fields that would later inspire the wild, mutated landscapes in her fiction. After earning a degree in physical education and realizing teaching wasn’t her thing, she joined the U.S. Navy (1950–1954), later pursued educational psychology, and eventually turned to writing science fiction while raising a large family.

Her first story, “Rocket to Gehenna,” sold to Fantastic in 1966, and Frederik Pohl championed her early work. Between 1973 and 1983, she published 13 novels and around 17 short stories—a concentrated burst of creativity that included titles like Star Rider, A Billion Days of Earth, Spaceling, and Doomtime. Her style? Think van Vogt’s chaotic plotting meets New Wave surrealism, with female protagonists navigating worlds where the environment is more alive and dangerous than any villain.

But Piserchia stopped publishing after 1983. Personal tragedy—her daughter’s death in 1984—pulled her away from writing, and she spent the rest of her life quietly raising her granddaughter in New Jersey. She died in 2021 at age 92, leaving behind a small but cult-adored body of work that’s only now getting rediscovered.

Earthchild: A Spoiler-filled Synopsis

Earthchild is set on a far-future Earth that’s been completely transformed by two warring, quasi-sentient ecological forces. Humanity fled to Mars centuries ago, leaving the planet to these titans. Our protagonist is Reee (two syllables), a feral teenage girl who believes she’s the last human on Earth.

The Last Girl on Earth

When Reee is only four years old, her mother is snatched away by a Martian rescue ship, leaving the girl alone in a lethal, alien wilderness. She should die quickly. But she doesn’t—because Emeroo takes an interest in her.

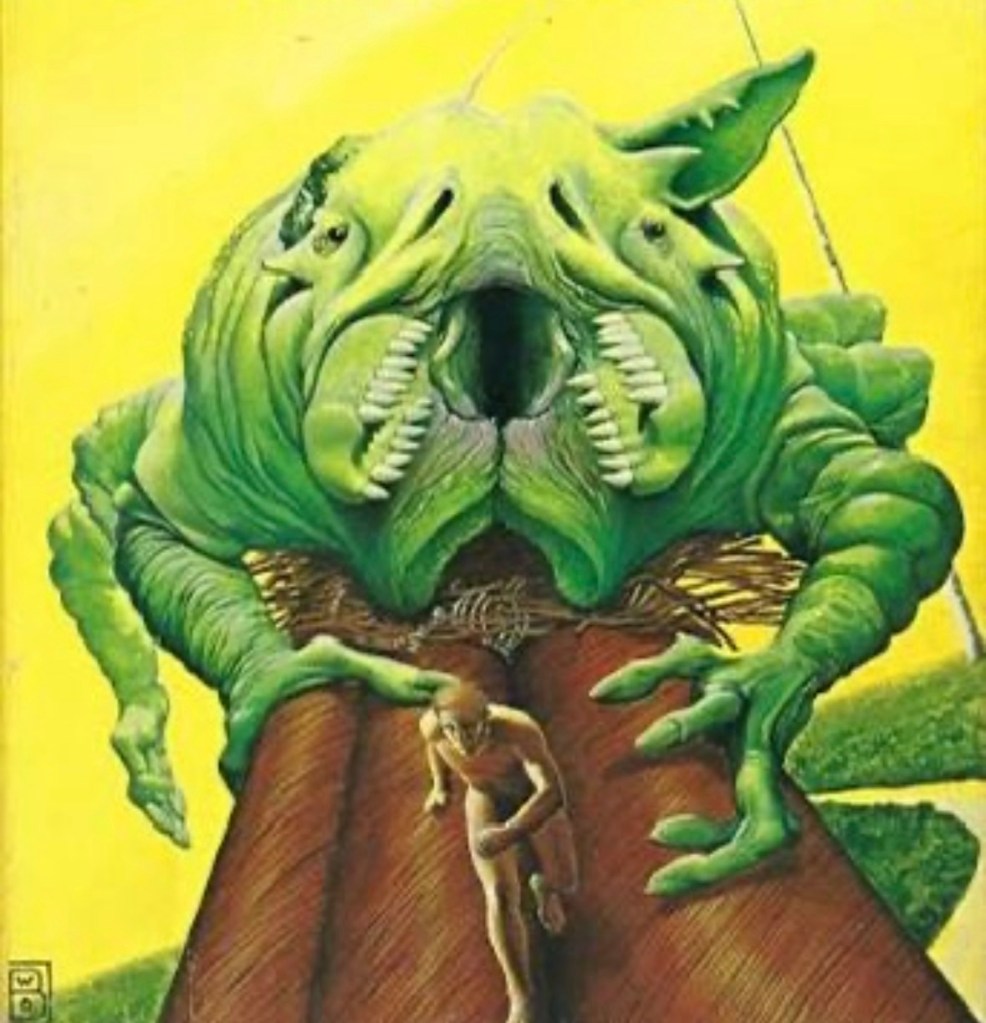

Emeroo is a near-omniscient, green, fungal-arboreal consciousness that can shape tendrils, bodies, and shelters out of itself. It’s protective. It shields Reee from predators, builds her shelter, and uses her as mobile eyes and ears in places it can’t reach directly. But Emeroo is also possessive and controlling, treating Reee more like a pet than a person. As Reee grows into adolescence, she learns to forage, fight, and navigate a world where the ground itself can be hostile or alive in nonhuman ways.

The other player in this planetary struggle is Indigo, a devouring blue protoplasmic ocean that’s spread across most of Earth’s surface. Indigo eats everything it touches—greedy, immature, and obsessed with expansion. It wants a foothold on Mars (the one place it can’t reach), so it creates “blue boys”—humanoid mimics grown from its substance—and tries to pass them off as human survivors so Martian rescuers will carry them off-world. Shades of Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, you might ask? Not quite, but it has some vague similarities.

Throughout the novel Reee makes it her mission to thwart Indigo’s expansion and to murder every blue boy she finds before Mars can be contaminated.

Cycles of Protection, Rebellion, and Time

Reee’s relationship with Emeroo is the emotional core of the book, and it’s intensely complicated. Emeroo protects her but also confines her. Whenever Reee pushes too far into danger or tries to assert her independence, Emeroo reacts by enveloping her and plunging her into deep hibernation—preserving her through centuries-long time jumps while the war between green and blue plays out.

After one such hibernation, Reee wakes to find Indigo has advanced dramatically. The world feels more alien and empty: creatures she knew are gone or transformed, and the balance of power has shifted again. She tries repeatedly to live on her own terms—leaving Emeroo’s protection, wandering, fighting blue boys, testing the limits—only to encounter fresh horrors or crushing loneliness that drive her back.

This cycle repeats. Protection, rebellion, punishment, sleep, awakening. It’s an allegory for adolescence if your overbearing parent was a sentient forest and the outside world wanted to literally digest you.

Martians, Myths, and Other Humans

To Reee, Mars is almost mythic—a sterile refuge world inhabited by small, stunted, half-mad people who abandoned “real” life for safety. Martian ships occasionally return to Earth, motivated by legends of the “Earthchild,” the last native human they want to study, rescue, or exploit. Reee fiercely refuses their help. She doesn’t want to be turned into a symbol or a specimen.

Her belief that she’s the only human alive starts to crack when she encounters another apparently human figure during one of her hunts. This opens a mystery: if she’s not alone, who’s been lying to her, and why? The answer fits Piserchia’s off-kilter logic more than conventional plotting—humans and near-humans appear in odd contexts, some shaped by alien forces, some locked into their own distorted relationships with the environment. “Humanity” hasn’t simply vanished; it’s splintered and adapted in strange ways.

Beyond Earth: Mars, Jupiter, and Transformation

Late in the novel, after yet another massive shift in Indigo’s reach, Reee’s situation changes enough that she finally ends up aboard a ship leaving Earth. She travels to Mars and discovers it’s exactly as barren and spiritually dead as she feared. The people there are diminished, cramped, living in a world with no wildness. Unimpressed and still restless, Reee pushes farther into the solar system—to Jupiter.

In Piserchia’s universe, Jupiter isn’t a gas giant but a solid desert world with its own culture. The inhabitants regard Reee as a quasi-divine figure, an emissary from the legendary, devoured Earth. They briefly worship her before fear and misunderstanding turn to rejection. She’s imprisoned in a pyramid-like structure, loses consciousness, and the narrative shifts again.

Reee awakens on a beach among people more like her than the Martians or Jovians—figures who seem closer to her in outlook and origin, suggesting a new stage of human or post-human evolution. The book doesn’t end with clean explanations or resolved cosmology. Instead, it closes with an impressionistic sense that Reee has finally reached a context where she belongs, after spending ages as an anomaly caught between warring ecologies.

Throughout, Earthchild treats plot like a series of surreal, time-skipping episodes rather than a tight causal chain. Reee cycles through dependence and rebellion while Emeroo and Indigo reshape the planet, and her eventual outward journey reframes her not as “the last human” but as the first exemplar of something new.

My Take: Surreal, Frustrating, and Unforgettable

Earthchild is a weird book. I mean really weird. The logic operates on dream rules—Reee survives things that should kill her because the entities “willed” it, or simply because the narrative moves with fairy-tale momentum. Some readers will find this maddening (and I’ll admit the middle section can feel repetitive: Reee gets in trouble, Emeroo saves her, repeat). But if you surrender to Piserchia’s hallucinatory rhythm, there’s something hypnotic here.

The ecological surrealism is the book’s greatest strength. Piserchia inverts “Man vs. Nature”—here, Nature has split into two warring god-like biomes (Green vs. Blue), and Man (Reee) is just a pawn in their struggle. The color-coding is stark and effective: green equals safety, stasis, vegetation; blue equals danger, consumption, fluidity. And Reee’s journey is about navigating the space between these absolutes while fighting for autonomy.

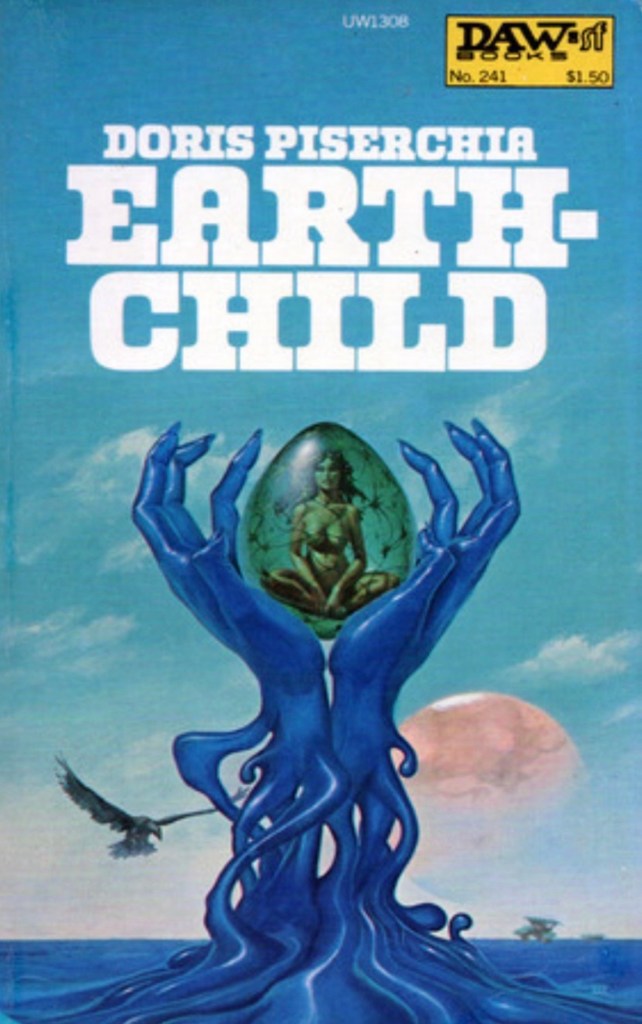

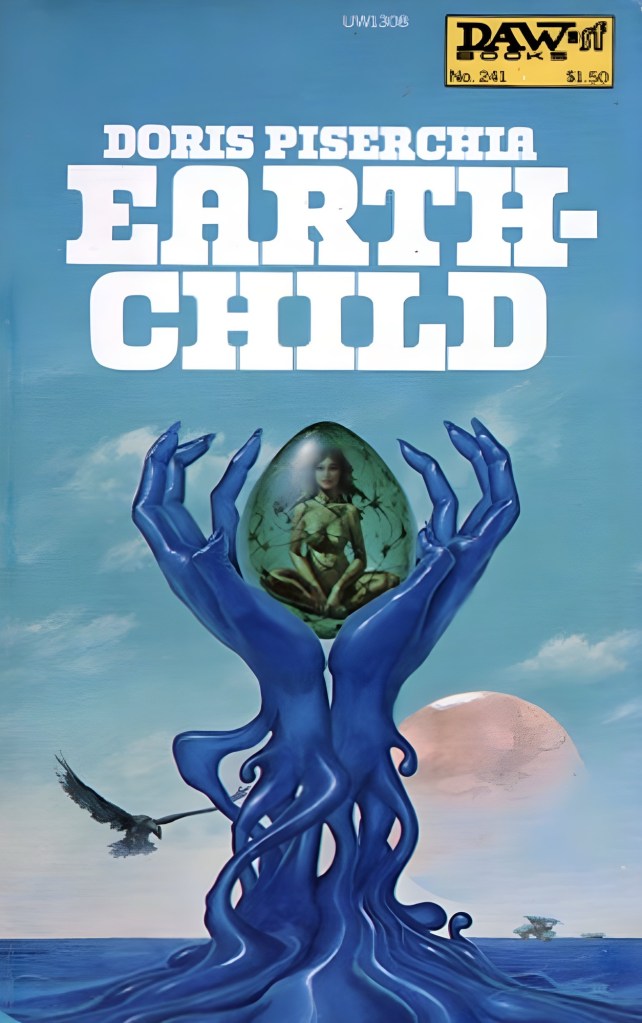

The Michael Whelan cover art? Absolutely stunning. It’s one of his best, and it perfectly captures the book’s alien, organic aesthetic. If you’re a collector of vintage DAW paperbacks, this one is worth hunting down.

But I won’t lie—the dialogue can be stilted, and the pacing is uneven. Piserchia was more interested in world-building and philosophical mood than tight plotting, which means some scenes drag while others rocket forward at breakneck speed.

Who Should Read Earthchild?

This book is for you if you love:

- Dying Earth subgenre (Jack Vance, Gene Wolfe)

- Surreal, biological sci-fi (Jeff VanderMeer, early Brian Aldiss)

- Stories that feel like dark fairy tales more than hard science fiction

- Female protagonists who are feral, stubborn, and refuse to be rescued

- 1970s psychedelic New Wave SF that doesn’t follow standard templates

It’s not for you if you need tight plotting, hard science, or conventional character arcs.

Coda

Earthchild won’t be everyone’s cup of tea, but I’m glad I read it. Piserchia deserves to be remembered alongside the other weird, inventive voices of 1970s science fiction—Lafferty, Le Guin, Delany. She was writing wild, ecologically conscious, female-centered SF decades before it became fashionable, and Earthchild is a perfect showcase for her particular brand of genius.

Is it a masterpiece? No. But it’s a cult classic for a reason. If you’re tired of the same old space opera formulas and want something that feels genuinely alien, track down a copy. Just be prepared for a reading experience that’s more fever dream than adventure story.

Earthchild is currently out of print in physical formats but available as an ebook through Amazon and Kobo, or via second-hand sellers specializing in vintage paperbacks. Worth hunting down if you’re a fan of forgotten sci-fi gems.

*Thanks for reading, Fear Planet denizens! If you want to revisit, save, highlight, and recall this article, we recommend you try out READWISE, our favorite reading management and knowledge retention app. All readers of Fear Planet automatically get a 60-day free trial.

This post was blasted into the social media stratosphere by HopperHQ, the best social media manager out there.

*This post contains affiliate links. Purchasing through them will help support Fear Planet at no extra cost to our readers. For more information, read our affiliate policy.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.