One thing you need to know about Bob Pepper: he had a reputation as the rare cover artist who actually read the books he illustrated.

I know that sounds like the bare minimum—like saying a surgeon washed their hands—but in the paperback gold rush of the 1960s and 70s, it absolutely was not standard practice. Art directors handed painters a two-sentence synopsis, a tight deadline, and maybe a “make it look spacey” note scribbled on a napkin. The result? A lot of chrome rockets, a lot of blonde women in improbable silver bikinis, and almost zero connection to what was actually happening inside the book.

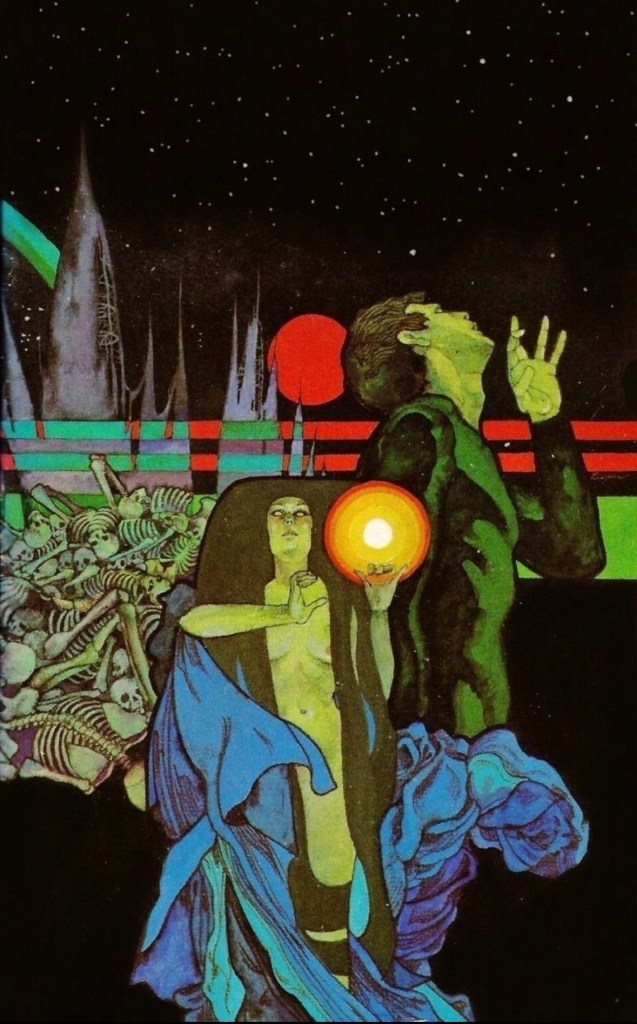

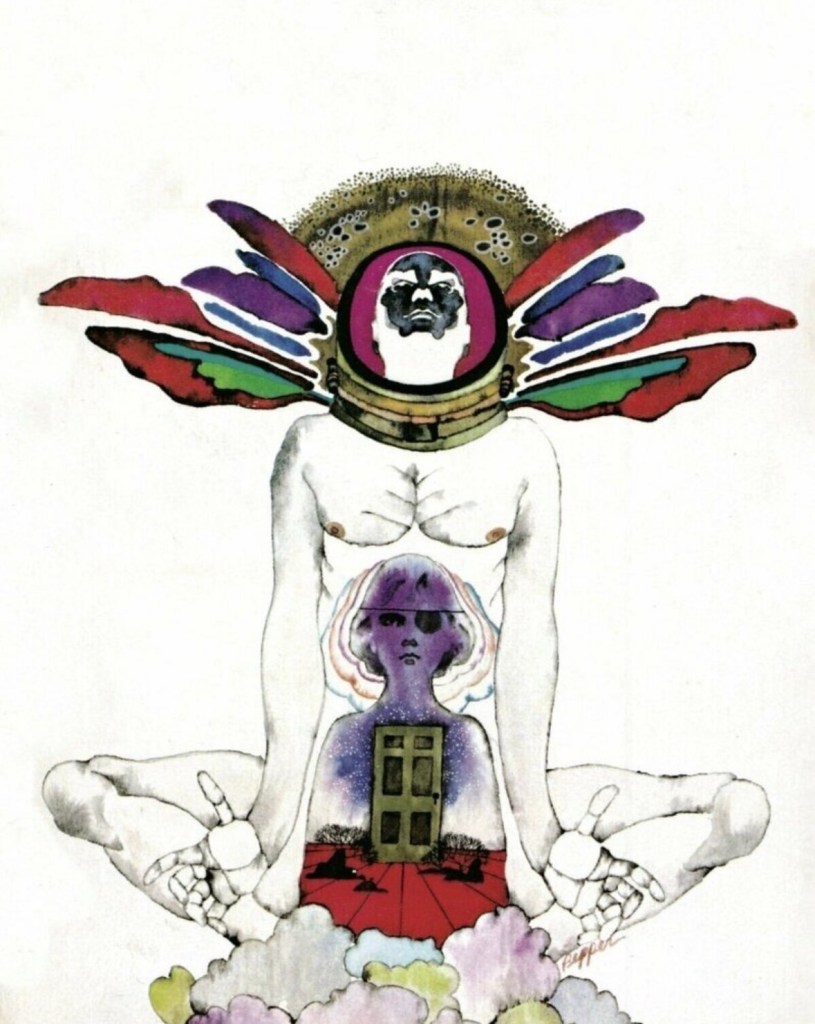

Pepper’s cover for The Omega Point by George Zebrowski

Pepper did something radical. He preferred to read the novels first, and he talked about “bringing together many different parts to form a coherent whole design.” That phrase is doing serious work. It means he wasn’t just decorating a product. He was interpreting it.

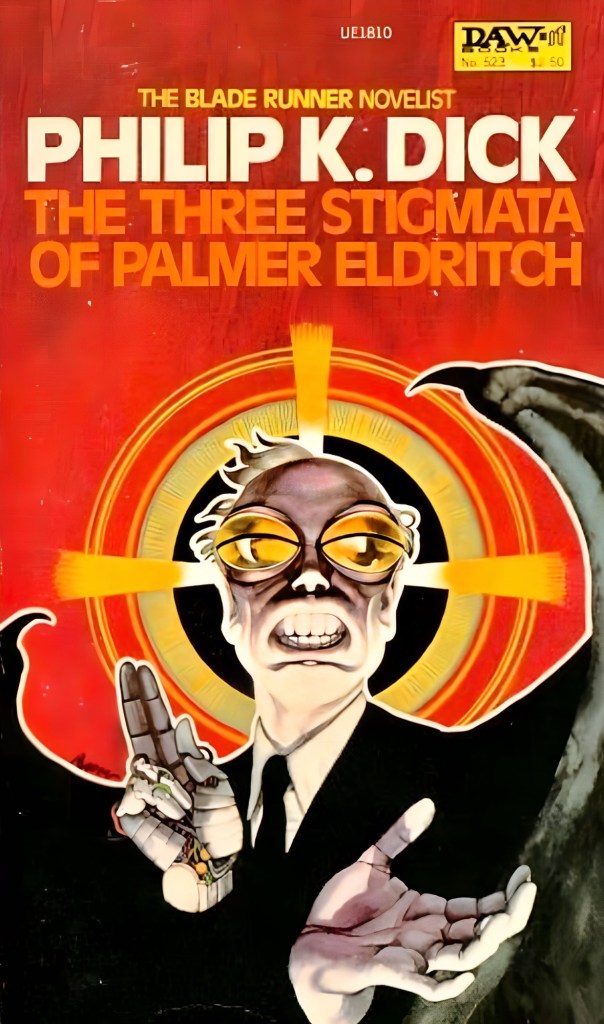

This matters because it changes what his covers actually are. They’re not generic psychedelic wallpaper slapped on random paperbacks. They’re genuine visual responses to specific texts. When you pick up his cover for Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, you’re not seeing “cool space stuff.” You’re seeing the three stigmata—the metal teeth, the mechanical arm, the artificial eyes—turned into a frontal icon, a false god staring back at you before you crack the spine.

Reading first meant Pepper could make the cover argue with the text, complete it, warn you about it. His images weren’t promotional. They were criticism in paint.

Which is why, fifty years later, his covers still feel like they know something you don’t.

The PKD Covers: Theology as Technology

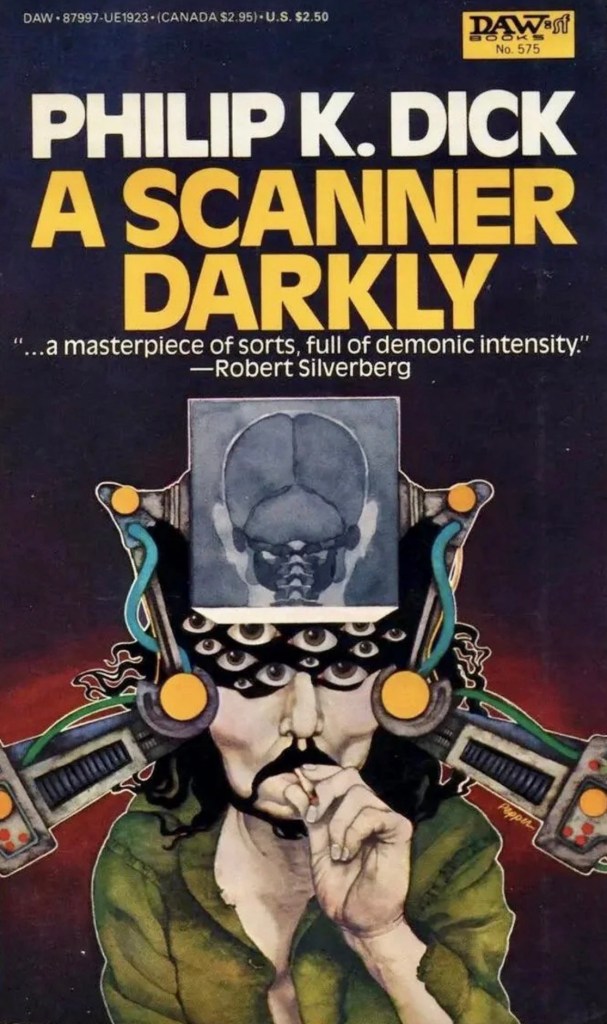

Let’s start with the Philip K. Dick run for DAW in the early 80s, because that’s where Pepper’s approach gets genuinely weird in the best possible way.

A Scanner Darkly (1984) puts a wired-up stoner right on the cover because that’s what the book is: surveillance, drugs, and the way your brain can betray you. Erik Davis—one of the only critics to write seriously about Pepper’s SF art—describes this cover as “drip[ping] with the hazy aura of American freak culture in the 1970s.” The central figure is a long-haired, mustachioed guy with desperate eyes, wearing brain-scanning gear, lit in trippy, melting colors.

But here’s the clever bit: that figure is both character and reader. Davis argues he’s a “white male long hair getting high, seeing through other eyes, and sinking into the sort of cavernous headphones favored by PKD and other audiophiles of the era.” The double role matches the book’s structure perfectly. Arctor is both user and narc, both “Bob” and “Fred,” both subject and surveillant. Pepper’s wired-up head literalizes that split. It’s a single body flooded with signals from elsewhere, and the tangle of cables hints at an apparatus that’s simultaneously technological and psychological.

(I love that Davis points out Pepper “puts the drugs out in the open” by painting an unapologetic stoner, not abstract swirls. Substance D is at once sacrament, anesthetic, and weapon—the cover’s trippy color field captures that ambiguous high.)

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1983) goes even harder into the religious iconography. Retrobookcovers notes that the DAW edition “prominently features the three stigmata”—the metal teeth, mechanical arm, and artificial eyes that mark Eldritch’s body. Those stigmata become the visual signature of a false god in Dick’s novel. Eldritch’s presence infects the Chew-Z hallucinations; reality itself becomes suspect, nested, possibly under the control of something neither human nor benevolent.

Pepper pulls those features into a totemic face. The composition is front-on and iconic, like an Eastern Orthodox icon or a tarot trump, with the three markers arranged almost as heraldry. That maps cleanly onto the book’s theological thrust—Stigmata imagines a god who’s more like “a shifty evil businessman” than a loving father. Pepper turns Eldritch from a plot function into a cult object the reader must face before even opening the book.

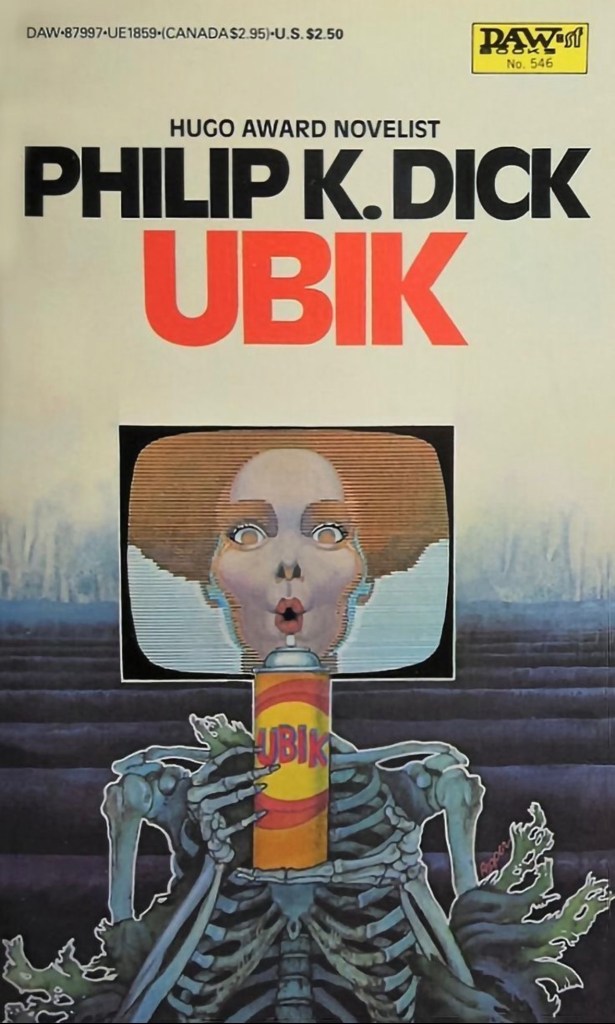

Then there’s Ubik (1983), the DAW cover of which is now one of the most widely shared images of the novel. The book’s about Joe Chip and his fellow “inertials” sliding into a reality that’s regressing in time—dead people linger in “half-life,” and salvation appears as a miraculous spray product called Ubik.

Pepper’s design picks up the fragmentation beautifully. The central head is transposed on a screen while the skeletal body is spare of flesh, mirroring the way time and identity dissolves in the novel. Characters and objects “revert” to older states. Joe Chip is never sure whether he’s alive or in half-life.

The face on the screen becomes the label of an unnamed, all-purpose salvific technology. That’s perfect for a book whose gag is that Ubik is advertised like a household good but functions like sacrament.

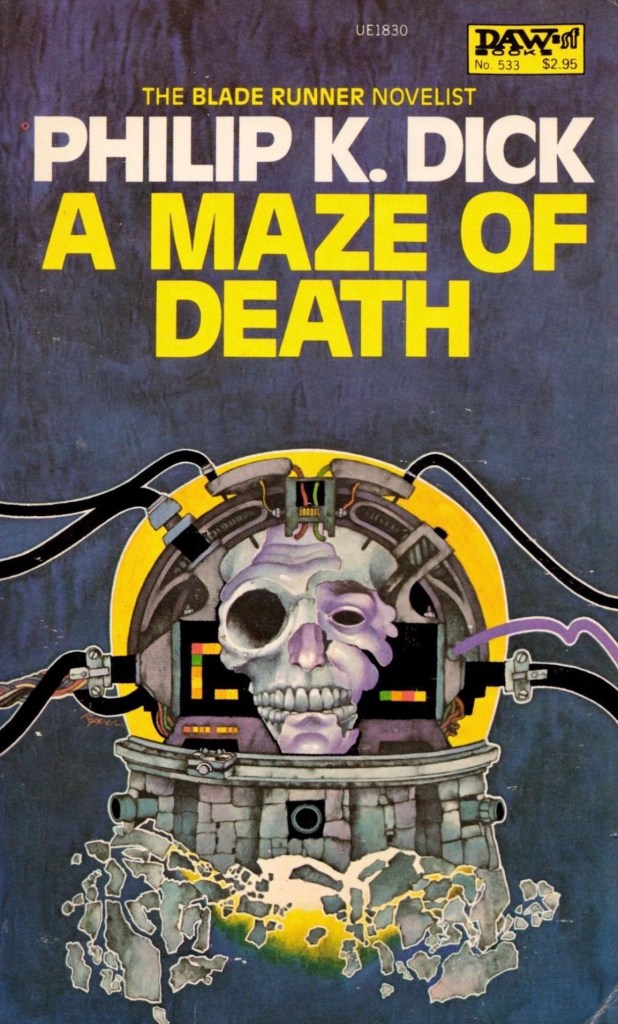

A Maze of Death (1983)—BiblioKlept calls it “messy space horror”—strands colonists on an inescapable world where a bizarre improvised theology, strange manifestations, and mounting paranoia lead to murder and a bleak revelation about the nature of their reality. Pepper’s cover, with its head in a bowl with a cluster of wires attached – while on a display stand of sorts – turns the technology of the setting into a type of eidolon, a visual fusion of machine and shrine.

The face on display speaks to how the characters in the novel are trapped in roles inside someone else’s “program,” their personalities flattened by the machinery of the plot. It’s a nice contrast to, say, a literal spaceship or planet landscape—Pepper illustrates the theology and trap instead of the physical setting.

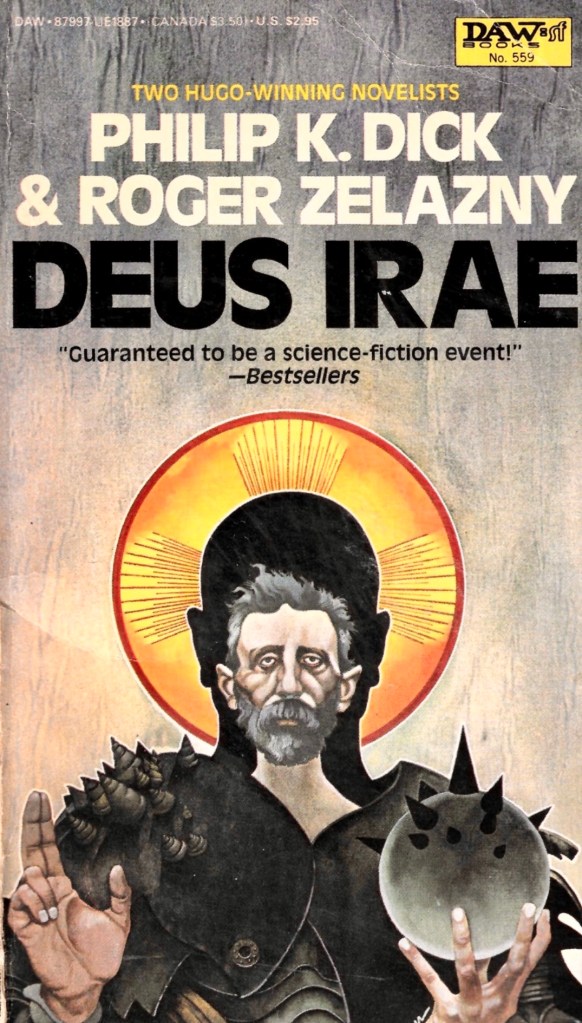

Deus Irae (1984), co-written with Roger Zelazny, is explicitly theological SF: a post-apocalyptic quest for the mysterious God of Wrath blamed for nuclear devastation. Pepper’s cover continues the religious strand with hybrid sacred/technological imagery—a Jesus-like figure, a golden halo, a black silhouette of some dark controlling entity, and armor suggesting mechanical might. It’s a world where the divine has become indistinguishable from weapons and infrastructure, which is the exact premise of a god who acts through thermonuclear fire.

This is Pepper extending his “false icon” vocabulary from Three Stigmata into a more overtly Christian-coded apocalyptic setting, where the problem isn’t absence of God but the terrifying possibility that God exists and is monstrous.

Beyond PKD: Other Paperback Prophets

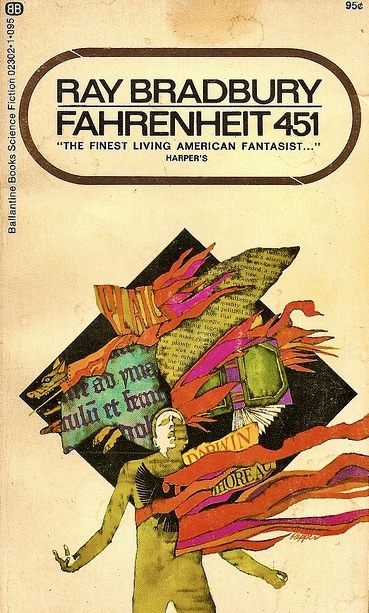

Fahrenheit 451 (Ballantine, 1969)—Bradbury scholarship confirms the 17th printing credits Pepper as cover artist, making this one of his most important SF assignments outside Dick. The cover shows a stylized, elongated human figure engulfed in paper-like flames. It’s a very Pepper take on an already iconic text.

Earlier covers by Joe Mugnaini turned Montag literally into a burning man made of print. Pepper pushes toward abstraction: the figure reads more as any human in the system—fireman, victim, reader—caught in the blaze of state censorship. The angled stance and stretching limbs feel precarious, mirroring the book’s tension between obedience and awakening. Pepper de-particularizes Fahrenheit 451. Where earlier designs belonged to a mid-century visual world, his version packages the novel as a timeless parable of state violence against the preservation of memory.

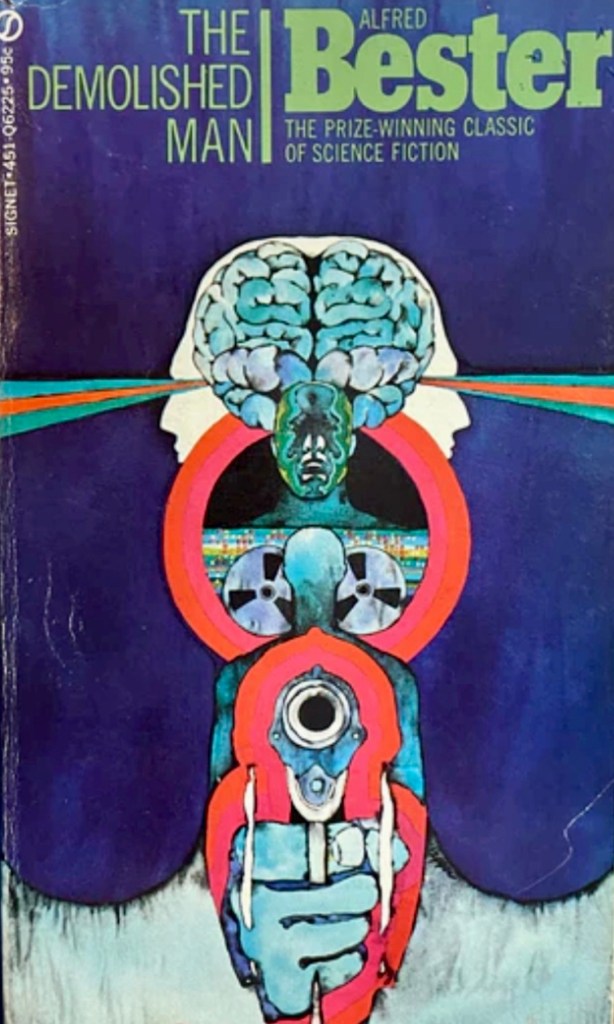

The Demolished Man (Signet)—ISFDB confirms Pepper as cover artist for at least one Signet edition of Bester’s telepathic police procedural. The novel’s about Ben Reich plotting a murder in a world where “peepers” make homicide almost impossible. Reich is haunted by “The Man With No Face,” a nightmare figure symbolizing guilt and fear.

Pepper’s tendency to flatten or mask faces works perfectly here. A cover figure with obscured or overlaid features can be Reich, the faceless man, or an Esper probing a mind. Abstract circular motifs, rays, concentric lines translate into visual shorthand for telepathy and psychic pressure. Pepper doesn’t show a chase or murder—he shows what it feels like to have your mind under continuous, invisible surveillance.

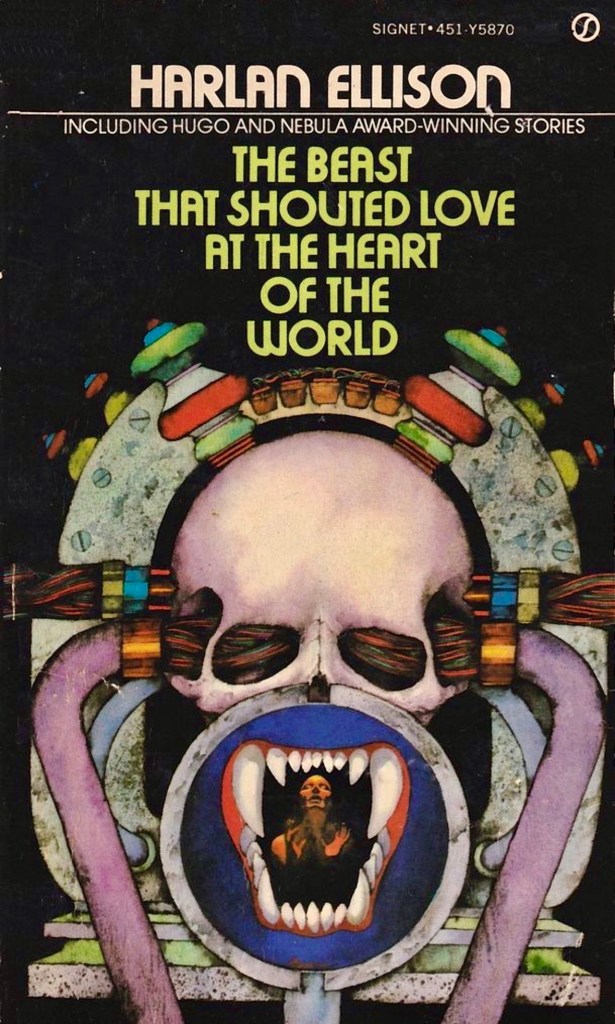

The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (Signet, 1974)—this Ellison collection cover gets compared to Giger and to the biomechanical artwork for ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery. That’s fair. The image fuses flesh and machinery into a screaming, composite head that looks like it’s been assembled from spare parts and bad dreams.

Ellison’s title story imagines the cosmos as a psychic dumping ground where one group purges its hatred and madness into “lesser” beings. Pepper’s screaming face, composed of multiple planes and compartments, visualizes many consciousnesses or emotions compressed into one monstrous whole. Tubes, grills, and hard edges turn it into an engine or weapon—not just an organic beast but systematized horror. It’s cosmic anger caged in technology, shouting through a rictus grin.

(Honestly, this might be my favorite of the bunch. It’s what Ellison’s prose feels like.)

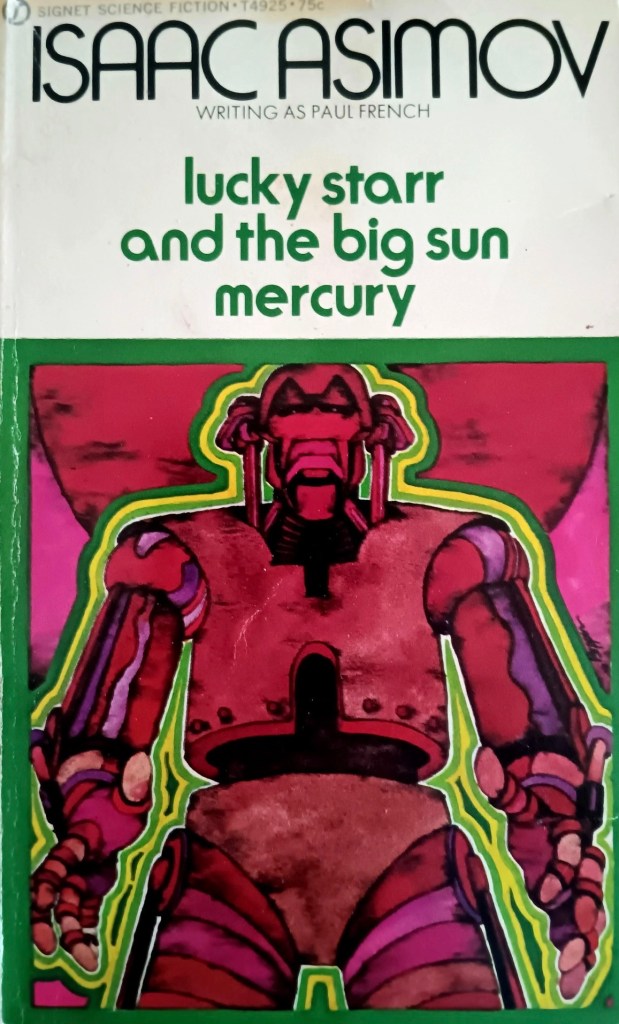

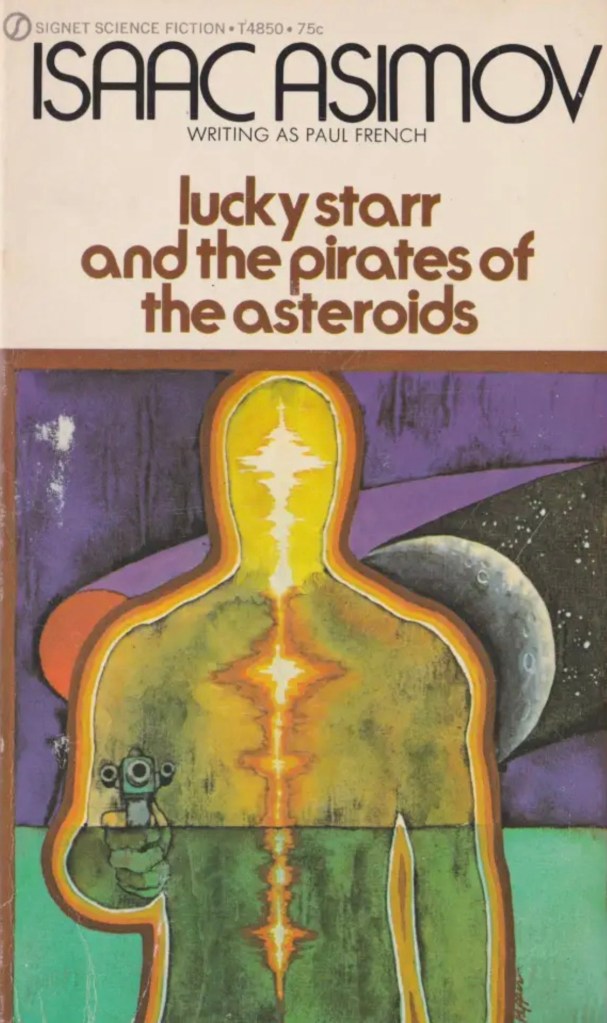

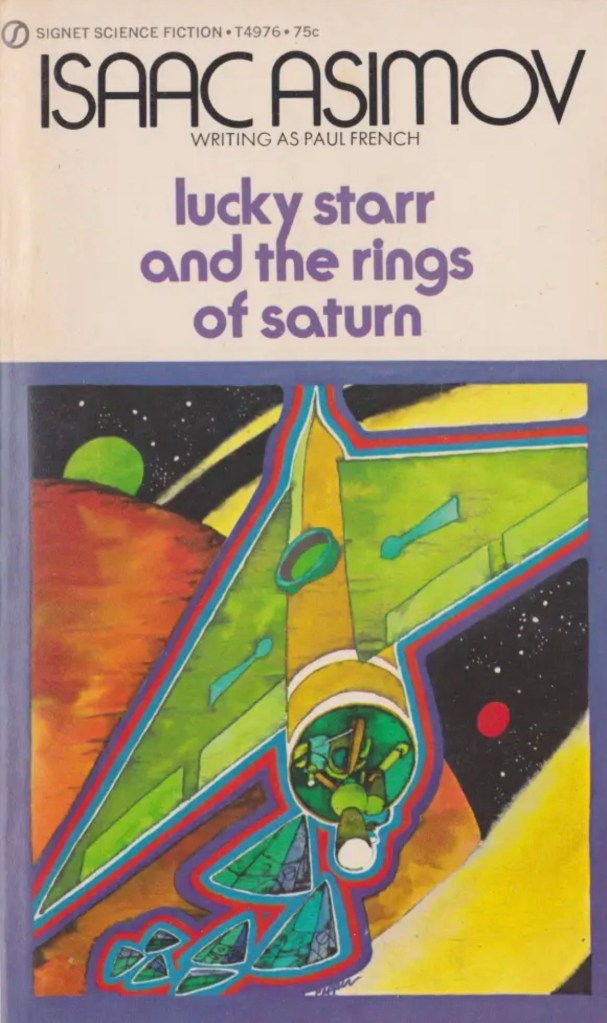

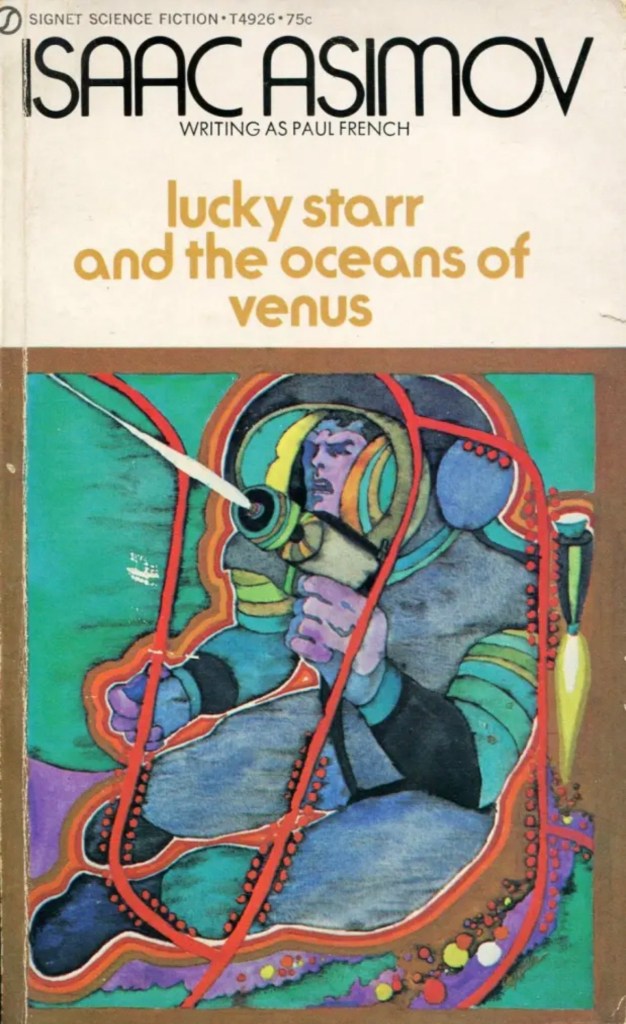

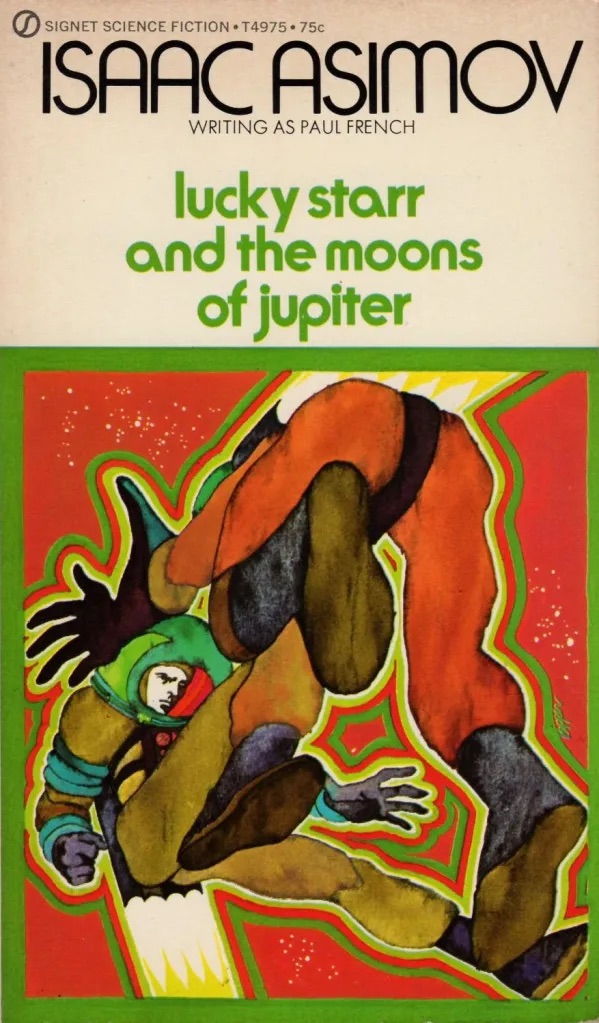

The Lucky Starr Rebrand

Finally, the Lucky Starr sequence (Signet, 1971-72). We Are the Mutants does a nice job framing these historically: Signet reissued Asimov’s juvenile novels “clearly intending to lure the growing science fiction community—by now largely resistant to black and white morality tales—with Bob Pepper’s radiant, kinetic images.”

The books themselves are straightforward pulpy adventures—Lucky Starr and the Big Sun of Mercury, …Moons of Jupiter, …Rings of Saturn. But Pepper’s covers do something conceptually ambitious. Lucky becomes less a person than a stylized emblem: repeated pose, simplified body, embedded in cosmic geometry. That mirrors his narrative function as a pure vector of rational competence rather than a psychologically deep character.

There’s also the matter of suggestive abstraction. Reddit threads have joked about the Moons of Jupiter cover, where Lucky’s pose and surrounding arcs “certainly resemble moons,” to the point that some editions were sold with a price sticker covering a suggestive area. This is very Pepper: the human form becomes pattern, and pattern becomes slightly erotic, slightly comical cosmic design.

The original books are Cold War allegories with alien stand-ins for geopolitical foes. Pepper’s swirling rings, sunbursts, and starfields reframe those conflicts as mythic ordeals—a visual update from 50s rocket-boy yarn to 70s “cosmic consciousness” SF. It’s a perfect case of how cover art can re-position a work generationally, making Asimov’s kids’ serial look like something you’d shelve next to New Wave head-trips.

The Importance of Bob Pepper

Look, I could talk about Pepper’s recurring devices all day—the centrally framed heads, the icon-like compositions, the technicized halos. But what really sticks with me is that he treated the science-fiction paperback as a site of modern icon painting. Small, disposable religious-psychedelic objects for readers of Dick, Ellison, and Asimov.

He turned Palmer Eldritch into a false god you had to worship before reading. He made Joe Chip’s dissolving identity visible from across the bookstore. He painted Lucky Starr as a cosmic glyph and Montag as an abstract burning offering.

And he did it all by reading the books first (Well, most of them, as far as we know).

That sounds simple. It shouldn’t be revolutionary. But in an industry churning out product at high speed, it was a quiet act of rebellion. Pepper’s covers say: This book is worth understanding. It has ideas. Let me show you.

Fifty years later, those covers still work because they’re not trying to sell you a rocket ship. They’re trying to sell you a vision—and they’re honest about how strange, uncomfortable, and beautiful that vision might be.

Discover more from Fear Planet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.